Recent livestock disease cases in WA

Eperythrozoonosis causes death in 30 lambs in the Great Southern

- Lambs still on their mothers presented with anaemia and sudden death.

- Marking had occurred one month prior and lambs received 6-in-1 and erysipelas vaccination, selenium and vitamin B12 supplementation and were drenched against worms. Marking equipment had been cleaned with a disinfectant.

- Carcasses were pale with watery blood, enlarged spleens and mesenteric lymph nodes and thickened small intestines. A blood smear and PCV showed a marked regenerative anaemia and large numbers of Mycoplasma ovis (eperythrozoonosis).

- M. ovis is transmitted via blood (e.g. contaminated needles or surgical instruments) or biting insects such as ticks, flies, fleas and mosquitoes. In conjunction with nutritional stress and a heavy worm burden, the disease in lambs can be severe.

- Worm egg counts were negative, consistent with recent drenching, however the histopathological changes were suggestive of prior intestinal damage caused by worms.

- Deaths in this flock resolved without treatment. Good nutrition, parasite control and reducing handling stress of affected animals can reduce losses until animals recover.

- Consider M. ovis if there is anaemia, jaundice and deaths especially after stressful events and in young animals. Outbreaks of the disease have previously been seen more frequently in spring.

- Key samples: blood smear, EDTA – take samples from affected and unaffected animals.

- Read more on our website on eperythrozoonosis.

Weakness and death in lambs in the Wheatbelt due to pulpy kidney (enterotoxaemia)

- Eight 6-8 week old lambs became weak and died after showing unusual behaviour. At marking 5 weeks prior lambs had received a 3-in-1 clostridial vaccine and the flock was fed on hay, lupins and oats.

- Ileal contents tested positive for enterotoxaemia toxin. This was supported by a finding of pulmonary oedema and accelerated autolysis of the proximal convoluted tubules of the kidney. There was a significant roundworm burden.

- Given the abnormal behaviour, blood was tested for lead toxicity (reportable), which was negative.Pulpy kidney can occur in unvaccinated or incorrectly vaccinated sheep, where there is a sudden change to high carbohydrate, low-fibre feed (such as lush pasture/grain) and is more likely in sheep that are rapidly growing. A one-off vaccination is generally not sufficient to provide immunity in previously unvaccinated sheep and lambs. Read more on pulpy kidney vaccination.

- Differential diagnosis: lead toxicity (reportable) and polioencephalomalacia (Vit B1 deficiency) where there is abnormal behaviour. Sudden deaths can occur with fluoroacetate plant poisoning and anthrax (reportable), which also presents with bleeding from orifices.

- Key samples: 10mL fresh, ileal content, EDTA blood, fresh and fixed tissues (brain, kidney, lung, liver).

In early spring, watch for these livestock diseases:

| Disease | Typical history and signs | Key samples |

|---|---|---|

| Polioencephalomalacia |

| Antemortem:

Postmortem:

|

| Worms in sheep and cattle

|

| Antemortem:

Postmortem:

|

Assisting producers to prevent vaccination site abscesses

-

Abattoir inspectors have noticed a recent increase in the number of vaccination abscesses in sheep carcasses, which result in downgrading and removal of sections of a carcass at abattoir and reduced profits for the producer.

-

Abscesses are normally seen in the neck, rump, flank, back and inner thigh. Vaccinations should be given high in the neck away from prime cuts.

-

This Animal Health Australia factsheet may be useful to help discuss with your clients best practice for vaccinations.

Video highlights benefits of livestock surveillance

A new four-minute video highlights the benefits to WA producers and to the livestock industries when they call a vet to investigate livestock disease. The Animal Health Surveillance in WA video is available on Youtube.

Exotic disease in the spotlight: Peste des petits ruminants (PPR)

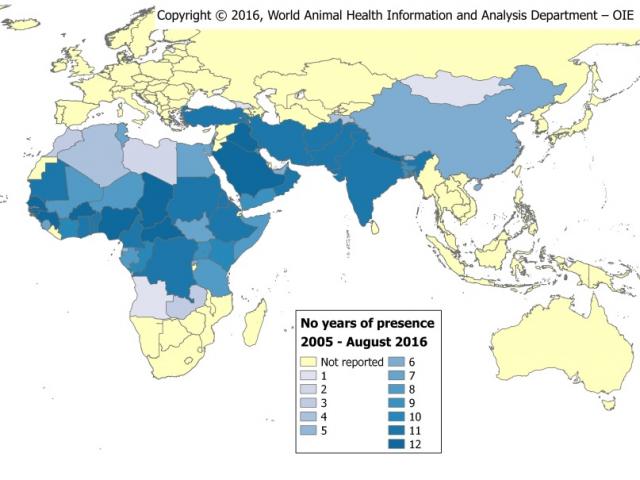

OIE map of the geographical distribution of PPR

Surveillance activities support Western Australia’s and Australia’s proof of freedom from specific diseases, increase our export trade opportunities and ensure that we able to detect exotic diseases in a timely way if they were to enter WA, so as to limit their impact. One of the serious diseases spreading in other sheep growing countries, and that Australia is currently free from, is peste des petits ruminants (PPR).

PPR is a highly infectious disease primarily of sheep and goats and is a member of the same family of viruses as rinderpest. The disease is well established in West Africa and extends into the Arabian Peninsula and Middle East but concern is mounting over spread further into central and southern Asia. In January 2017 an outbreak in Mongolia decimated a population of thousands of the endangered saiga antelope.

Differentials:

-

Bluetongue disease, foot-and-mouth disease, Nairobi sheep disease, sheep pox, coccidiosis, salmonellosis, orf.

There have been no occurrences of the disease in Australia to date and cases of disease in sheep or goats showing similar signs to PPR are tested to support Australia’s freedom from the disease and access to livestock markets.

Clinical signs:

-

fever, pneumonia, severe diarrhoea, high morbidity and mortality, inappetence, oral and nasal discharges, oral lesions.

What to do if you see signs:

PPR is a reportable disease in Australia. Contact your DPIRD vet immediately if you investigate a disease with these signs, or if your DPIRD vet is not available, call the emergency animal disease hotline on 1800 675 888.

Previous issues

Previous issues of WALDO - for vets and WALDO - for producers are available on the DPIRD website on the newsletter archive page or by searching 'WA livestock disease outlook - for vets'.

Feedback

We welcome feedback. To provide comments or to subscribe, email waldo@agric.wa.gov.au.