Dry ageing sheep meat for a premium price

Robin Jacob, DPIRD, South Perth

Author correspondence: robin.jacob@agric.wa.gov.au

The project

In 2018, the Sheep Industry Business Innovation (SIBI) activity co-funded with Meat & Livestock Australia (MLA) a project to investigate the potential of dry ageing. The aim being to add value to sheep meat from animals older than lambs (hogget and cull for age mutton). In 2018, Australia produced 230 000 tonnes carcase weight equivalent of mutton, equivalent to nearly one third of the total sheep and lamb meat produced. Flock structures in WA based on merino ewes for wool production tend to produce hoggets and mutton as well as lamb.

There were four components to the project:

- Guidelines for the safe production of dry aged meat

- Market insights study

- Eating quality and yield experiment

- Economic analyses

A range of people contributed but particular thanks go to the meat science teams at the University of Melbourne and the William Angliss Institute, Melbourne.

There were many findings across the different parts of the project. The following are some highlights only. The guidelines for the safe production of dry aged meat, produced after consultation with authorities in each state of Australia, are now available on the MLA website. Anyone wishing to undertake dry ageing should check this out here.

Comparing dry versus wet ageing

Weight loss due to evaporation and trimming for sale

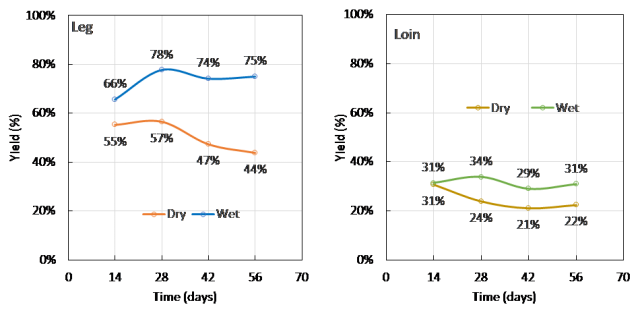

Ageing inherently caused more weight loss due to evaporation of moisture from the surface, than for wet aged mutton (Figure 1). For dry aged meat, the loss increased with ageing time and depended on the cut to some extent. Loin lost more weight than leg. The longer the ageing period the greater the weight loss in both cuts. Dry aged carcases also become increasingly more difficult to butcher as the ageing period increases, requiring more time and skill.

The commercial implications of this effect depended also on yield after deboning and fat trimming, the extent of which varied according to the cut and level of trim. The yield was lower with relatively more fat and bone removed from the loin compared to leg when prepared as a commercial cut (Figure 2). Therefore, the relative effect of dry ageing on yield was also less for loin compared to leg.

The effects of dry ageing and the length of the ageing period became even more obvious for the topside when totally denuded in preparation for sale as a single cut (Figure 3). Depending on how a butcher was to prepare a cut for retail and the length of the ageing period used, the price premium required to account for the weight loss due to dry ageing would vary. This is something that an individual business would need to determine for their own circumstances and marketing plan.

Eating quality

The project used several methods to evaluate consumer acceptance of dry aged mutton. The Meat Standards Australia (MSA) method formed the basis of the study to compare wet and dry ageing techniques. This used a standard shape of meat completely denuded of fat and grilled under standard conditions for temperature, before assessment by untrained consumers.

Consumer scores overall were high and within the premium category, at least for loin (Figure 4 ). This was a little unexpected but suggests that regardless of the method used, aged mutton could be valued as a table meat, if marketed and cooked appropriately.

Extending the ageing period beyond 14 days improved eating quality but not as much as was expected, from previous work on dry aged beef. Most importantly there was no difference between the ageing technique with consumers rating the meat the same for both dry and wet ageing. There was evidence from other qualitative studies with consumers that suggested differences in flavours that wasn’t detected in this wet versus dry comparison study.

Optimal aging period based on yield and eating quality

A shorter ageing period may be required for sheep meat compared to beef of 14 days to optimise tenderness for a minimal yield loss. The effect of ageing period on flavours requires further investigation.

Potential markets for dry aged mutton

The market insights work showed both a rapidly growing interest in dry ageing worldwide and an interest from chefs in both Perth and Melbourne. About 10% of the beef market in the USA is dry aged and is worth $10 billion annually. The type of consumers interested in dry aged meat are willing to spend more for meat. Any marketing campaign would need to target these groups known in the market as “voracious carnivores” or “selective foodies”.

A different cuts paradigm

The work with butchers and chefs identified ways to best utilise dry aged mutton in prepared meals as either “a centre of the plate” option or as part of a recipe. A range of dishes and recipes were prepared that can be used across a variety of restaurant formats from casual to formal dining.

Cuts considered premium may be different for aged mutton compared to lamb. For example, loin cutlets while easily fitting on a fine dining menu were relatively small and difficult to cook well after dry ageing. Cuts suited to either mince options or slow cooking methods, particularly shoulder and rump, achieved the best results. Chef feedback suggested these cuts could provide significant value add to a restaurant when considering the lunch meal occasion or more uniquely flavoured options pairing with indigenous flavours.

Industry economic analysis

Yield differences compared to wet ageing formed a major consideration for the economic analysis at the industry level. With the current data, the value of dry ageing to the industry was determined to be either small or equivocal to traditional selling methods. This would not warrant an industry scale investment in dry ageing facilities now so the opportunity to find ways to value add mutton unfortunately still exists.

Conclusions

Dry aged mutton is a safe and wholesome product when prepared correctly that can deliver a unique and premium eating experience. The recently developed guidelines outlines the systems needed to achieve this commercially. Due to the costs involved with weight loss and production, dry aged mutton will likely continue to be a specialist product, prepared by niche businesses and sold for a premium price. Whilst the “foodie” segment celebrating special occasions are the most obvious customers, some exciting opportunities still exist to add value to mutton as a more everyday product with the potential of demand increasing. If you are interested in any of the recipes, please contact the author.

![Smoked mutton round with purple salad and creamy fetta sauce. [Source: William Angliss, 2018] Smoked mutton round with purple salad and creamy fetta sauce. [Source: William Angliss, 2018]](/sites/gateway/files/styles/gw_large/public/Smoked%20mutton%20round%20with%20purple%20salad%20and%20creamy%20fetta%20sauce..jpg?itok=ekO_EN0r)