The WA NLIS Sheep and Goat Advisory Group – 12 months on

Beth Green, Chair and Livestock Identification & Traceability Manager, DPIRD

Author correspondence: beth.green@dpird.wa.gov.au

Introduction

The WA National Livestock Identification Scheme (NLIS) Sheep and Goat Advisory Group (SGAG) was established in November 2021 as a forum to discuss, consult, develop and communicate traceability enhancements across the commercial sheep and goat supply chain, and with non-commercial stock owners. While all components of traceability would be on the agenda, the impetus for forming the group was maximising the time for preparation for the expected national agreement to mandate individual electronic identification (eID) in sheep and goats.

Four meetings have been held over the past year, one in Katanning, with the fifth scheduled for 15 December 2022.

On 9 September 2022, all Australian Agriculture Ministers approved the implementation of the National Biosecurity Council proposal for eID for sheep and goats and agreed to work towards mandatory implementation in each jurisdiction by 1 January 2025.

A national Sheep and Goat Traceability Taskforce (SGTTF) has been convened and is developing harmonised national business rules and funding arrangements between the Commonwealth and the States. The SGTTF will report back to Ministers in December 2022 with progress.

One purpose of the WA Advisory Group is to make recommendations to DPIRD on how mandatory eID could be implemented for a well prepared and effective transition. This advice will be used to inform state government decision-making, including any requests to access national and state funding opportunities.

For DPIRD to receive additional funding from the WA Government for eID, a business case needs to be approved by the Minister and then submitted for consideration as part of the WA budget process. Developing the business plan in partnership with industry will give DPIRD the best chance of achieving a successful outcome.

Members of the Advisory Group consider that an effective traceability system, in addition to being economically beneficial, is of vital public interest for maintaining food security across the whole of the livestock industry, and agreed that this situation needs to be communicated as part of any business case for eID tag subsidies.

During the past four meetings, members of the SGAG have:

- Reviewed DPIRD commissioned reports on the implementation of eID in Victoria and on the supply chain infrastructure, tags and staffing required to mobilise eID in WA;

- Invited WA visual tag manufacturers to the discussion as a significantly impacted sector;

- Workshopped practical transition timeframes, activities and potential subsidies; and

- Considered how the whole industry can address areas for improvement in the other components of traceability with a co-branded communications package.

Discussions are summarised below.

Report one: Reviewing the Victorian program

ACIL Allen was commissioned to write two reports. The first was a review on the implementation of eID in Victoria and what could be learnt prior to beginning the journey in WA. Findings included:

- WA is currently functioning at a higher level of traceability than what Victoria started with, which should be taken into consideration when determining the implementation process, including transition timeframe.

- It is necessary to keep the year-of-birth colour system active for animal husbandry purposes.

- Once mandatory, all sheep should be tagged with an eID and all scanned at each location they move through (no staggered commencement dates or scanning rates for different locations after 1 January 2025).

- Tag rebates should be applied at the tag manufacturer level to reduce handling.

- Filling the nine proposed support staff positions could be difficult with a staffing shortage across all sectors currently.

- As many goat purchasers are non-commercial owners with limited agricultural experience, it would rest with studs and producers to meet the NLIS movement recording requirements on their behalf.

Report two: Cost to implement

The second ACIL Allen report provided cost estimates for implementing infrastructure through the supply chain, tagging lambs/kids, retagging existing stock and employing staff to support industry. The report will be one of several inputs, including data analysis and stakeholder engagement, that will help inform DPIRD’s final position on the costs of implementing mandatory eID.

A priority in both the review and future implementation is to maintain the flow rate of animals through the supply chain. Throughput and functionality to meet mandatory compliance was considered for the different sectors: producers, feedlots, saleyards, processors, livestock agency-run sales and export depots.

If government agreed to provide funding to support the purchase and installation of infrastructure, it would be allocated through a grants process. A contingency fund of $250 000 was included to address any requirements missed in the consultation process, or incorrectly estimated through extrapolation. The contingency fund would also be available for the establishment of contract scanning services.

Costs for producers are associated with the purchase of eID tags. The current flock size is around 15.3 million sheep, of which about 6.2 million are lambs and kids that will require a year-of-birth coloured tag. Approximately 3 million older sheep move each year, which would need re-tagging. Should NLIS device subsidies be made available, one calculation method used was based on 50% of net cost for an NLIS eID tag compared to a visual tag. Actual subsidies will be determined by how much funding is received, and the timeframe to access any subsidy.

Panel reader/scanner sets would be required for sheep as the tags are on either side of the head. Panels are relatively cheap, however the costs of installation and associated retrofitting into existing infrastructure needed to be considered. Costings were estimated as a guide, based on feedback received through consultation, and actual costs will be unique to each site and will require professional assessment.

Livestock agencies and Community Recourse Centres (CRCs) in sheep dominant areas will be considered for provision of handheld scanners for producer access if needed. These will build on the scanners already placed across the regions for cattle producers.

All funding allocated to the implementation of eID will be associated with making the system work to meet traceability requirements. It will not support optional infrastructure, such as hook tracking at processors or on-farm production management.

Tagging manufacturers

Accredited electronic NLIS tags can be found on the Integrity Systems website. At ordering, the species to be tagged is nominated (sheep or goats) and the tag details are uploaded accordingly to the NLIS database. As only one eID can be used at a time to avoid scanning interference, tags that are not accredited will need to be removed from 1 January 2025.

A & A Branding, Stockbrands, Swingertags/Tallytags and Pinnacle Products are aware eID was coming but not all are currently able to produce accredited eID tags. However, despite mandatory eID in Victoria, producers are still requesting visual tags for their on-farm management of livestock.

Patricia Forehan from Stockbrands explained the difficulties in achieving an NLIS approved eID product, which took them three years for full accreditation.

Those producers who already use electronic identification have noted that 6weeks was a realistic delivery timeframe, but it had been extended with increased demand coupled with a worldwide shortage of transponders (microchip in the eID tag). Producers must be organised with their orders to ensure they are received on time.

While only one eID tag can be used on an animal, visual tags can still be used for management. Year-of-birth coloured visual tags should still only be used in the correct ear for gender, especially if they look exactly like an eID tag. It is illegal to use a tag that causes confusion with required year of birth or pink tags.

It is not possible to recycle the electronic tags from abattoirs without damaging the transponder in the removal process. The transponders are locked and cannot be re-used within the same industry for 20 years. The amount of copper within the tag is not worth the process of extracting it.

Goat hock bands

The Goat Industry Council of Australia (GICA) have been working for several years to find an alternative identification method for dairy goat breeds, miniature and earless goat breeds.

The use of standard NLIS devices in dairy goats has been problematic due to the adverse reactions that can occur in their ears. Miniature and earless goats have been included due to the physical difficulties in applying tags to small ears or in the absence of ears.

An eID hock band in a single colour of yellow, or pink as required, has been approved to be fitted around the rear leg of goats. It can be expanded for animal growth but cannot be retracted back in. Owners of these breeds will still be able to use eID ear tags if they choose to.

Co-branding communication material

From the first Advisory Group meeting, the disconnection across the supply chain in communicating and understanding the responsibilities under WA’s current traceability system was discussed. WAFarmers proposed that a co-branded communications package would be worthwhile for consistent messaging across the supply chain, which aligned with the PGA’s concern that focussing on changing just the tag type would not improve the whole traceability system.

Some of the issues to be covered by the co-branded program include:

- Incomplete, illegible and outdated NVD waybills: a common problem along the supply chain which makes it difficult for accurate information to be entered in the NLIS database.

- Expired stock owner/brand registrations (and then LPA): extremely time-consuming at abattoirs, saleyards and export depots.

- All properties with stock need to be registered with a Property Identification Code (PIC).

- Identification: planning to make sure all stock are correctly identified prior to leaving the property.

- The NLIS database: irregular use by many producers makes it difficult and time-consuming when they do; lack of awareness of need to record movement to a new PIC on the NLIS database within the 48-hour timeframe.

Material that explains the ‘how’ has been developed for business operators to distribute to clients and vendors. The Where’s Woolly video has been developed to explain the ‘why’.

Following that meeting and the Ministers’ decision to approve the mandating of eID, the development of FAQs and a webpage are being progressed to address the key questions and provide familiarity with the eID system.

Transition workshops

Significant discussion has been held on which aspects need to be implemented first, and how each year will follow. Now that there is a target date, the proposed plan has progressed but will depend on availability of funds to commence and be more definite.

In general, the WA plan relies on providing incentives for producers to start using eID tags (during lamb and kid marking in 2023 and 2024) in preparation for the 1 January 2025 mandatory implementation date, while preparing the downstream supply chain with readers and infrastructure to be up and working by the due date. In this way, both the tagging and infrastructure come together in time for a successful implementation.

The use of a single colour eID tag to identify existing stock on property (in addition to keeping any visual tags) prior to movement off property would ease the burden for manufacturers in the short-term and be more practical than having to re-tag, for example, a green tagger with a green eID, and purple with purple. In this regard it was noted that:

- A non-year of birth colour would not be suitable, as estimating the number required would be too difficult and any surplus could not be used.

- Yellow was generally accepted as the best colour as it won’t return to use until 2029, it is the standard colour NLIS tag for sheep in the eastern states and any surplus – held by manufacturer or producer - could be kept for later use.

The time to having all existing sheep on property eID tagged has not been discussed. 1 January 2025 is when all sheep and goats moving off their properties of consignment and all lambs/kids born are electronically identified and will be scanned as they make their way through the supply chain.

A tagging subsidy needs to consider:

- how long a subsidy would ideally be provided for, noting a longer time would likely result in a smaller subsidy rate

- when the best start date for the subsidy would be, relative to the transition period prior to 1 January 2025

- whether the subsidy rate should be fixed or variable over the period.

Members agreed that the longer the time available for preparing for the new system the better, with a minimum 12 months necessary for ensuring all infrastructure, hardware and software systems are in place and functioning. It was suggested to break down the time prior to 1 January 2025 into a six-month installation and training period (Jan - June 2024) and a 6-month trialling and testing phase for feedlots, abattoirs, saleyards and export depots (Jun-Dec 2024).

Implementation of infrastructure and hardware grants could be deployed retrospectively (on invoice/receipt), or prospectively (on business case and quote); single orders (per business) or bulk (multiple businesses).

Several producers have already transitioned to eID which could be useful in trialling animals moving through the entire supply chain to identify any issues in advance. The ability to demonstrate real movements to others will help to show the benefits in traceability for individually identified animals.

SGTTF Round Table

Two SGAG members; Steve McGuire as State Farming Organisation representative (WAFarmers) and Steve Wainewright as Supply Chain representative (Saleyards), meet with the SGTTF virtually for national Round Table State Producer Group meetings. Two have been held so far, reviewing the background to the decision to mandate eID and to see the outcomes of the federal co-design program which has generated material to assist industry in understanding their requirements under the NLIS Sheep and Goats.

Next meeting

The next meeting of the WA Sheep and Goat Advisory Group will be held on 15 December 2022 in Perth. If you are interested in attending along with your usual industry representatives, please phone Executive Officer, Jemma Thomas, on 0459 850 569.

Abortion and lamb mortality between pregnancy scanning and marking for maiden ewes

Thomas Clune, Amy Lockwood, Serina Hancock, Andrew N. Thompson, Sue Beetson, Caroline Jacobson (Murdoch University), Angus J. D. Campbell, Elsa Glanville, Daniel Brookes (University of Melbourne), Colin Trengove and Ryan O’Handley (University of Adelaide), Gavin Kearney (Biostatistics Consultant)

Author correspondence: c.jacobson@murdoch.edu.au

Introduction

The reproductive performance of maiden ewes is an important component of overall flock performance in Australia given maidens represent 20–30% of breeding ewes. Studies conducted mainly in adult and mixed age flocks indicate lamb mortalities in the perinatal period (during or close to birth) are a major source of reproductive inefficiency for Australian sheep enterprises. Some overseas studies have shown that abortion during mid- or late- pregnancy may be an important contributor to the reproductive inefficiencies of maiden ewes. However, the timing and causes of foetal and lamb mortality between pregnancy scanning and marking for maiden ewes has not been well studied.

Aims

The aim of this study was to measure abortion and perinatal lamb mortality from maiden ewes joined either as ewe lambs or hoggets.

Methods

This study was conducted using 30 maiden ewe flocks on 28 farms across Western Australia (11 flocks), South Australia (9 flocks) and Victoria (10 flocks).

Approximately 200 maiden ewes were monitored from joining to lamb marking on each farm. Nineteen flocks were mated as ewe lambs (7–10 months of age at joining) and 11 flocks were maiden Merino hoggets (18–20 months of age at joining).

Ewe lambs were of non-Merino breeds except for one site in Western Australia, which joined Merino ewe lambs to Merino rams. Sires were all the same breed as ewes except for two flocks of Merino hoggets that were joined to White Suffolk rams.

All rams were confirmed to be negative for Brucella ovis (brucellosis) by blood test prior to joining and were naturally joined with a ratio of approximately 50 ewes per ram, for an average of 38 days.

The study involved observations and measurements including ewe liveweight and condition score at timepoints between joining and lamb marking;

- Joining

- Pregnancy scan 1 (62–101 days)

- Pregnancy scan 2 (108–136)

- Pre-lambing

- Lambing (lamb data only)

- Lamb marking

Reproductive rate (% foetuses expressed per ewe joined), mid-pregnancy abortion frequency (%), and foetal and lamb mortality between Scan 1 and marking were calculated (%). Estimates of mid-pregnancy abortion between Scans 1 and 2 and estimates of overall mortality from Scan 1 to marking were assessed by fitting generalised linear mixed model. Lamb mortality (%) between Scan 1 and Scan 2, Scan 2 and birth and birth and marking within flocks were compared using a 2-tailed Chi-square test.

Results

The timing of foetal and lamb mortalities for the maiden ewes are shown in Table 1.

| Ewe lambs | Maiden hoggets | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Range | Mean | Range | |

| Conception rate (%)1 | 73 | 45 – 92 | 87 | 58 – 97 |

| Scanning rate (%)2 | 113 | 58 – 156 | 105 | 60 – 135 |

| Mid-pregnancy abortion |

|

|

|

|

| % foetuses3 | 5.5 | 0 - 48 | 0.8 | 0 - 3.7 |

| % ewes4 | 5.7 | 0 – 50 | 0.9 | 0 - 4.4 |

| Foetal loss between scan 2 & birth (% foetuses)5 | 10 | 0 - 28 | 10 | 0 - 40 |

| Lamb mortality between birth & marking (% lambs)6 | 18 | 9 - 28 | 19 | 11 – 26 |

| Overall foetal/lamb mortality between Scan 1 & marking (% foetuses) | 36 | 14 – 71 | 29 | 20 – 53 |

1 Number of ewes pregnant at Scan 1/number of ewes joined (%)

2 Number of foetuses identified at Scan 1/number of ewes joined (%)

3 Number of foetuses lost between Scan 1 and Scan 2/number of foetuses identified at scan 1 (%)

4 Number of ewes with foetal loss between Scan 1 and Scan 2/number of ewes joined (%)

5 Number of foetuses present at Scan 2 but not accounted for at lambing/number of foetuses identified at Scan 1 (%). Includes lambs that were born and not recovered at lambing rounds (i.e., lost to predation).

6 Number of lambs that died between birth and marking/number of foetuses identified at Scan 1 (%). Includes full-term lambs dead at birth.

Ewe lambs

On average, 36% of foetuses identified at Scan 1 failed to survive to lamb marking, with lower mortality for lambs scanned as singles (24%) compared to lambs scanned as multiples (twins or triplets; 31%).

Mid-pregnancy abortion was detected in 14/19 (74%) flocks. In these flocks, mid-pregnancy abortion was detected in 2–50% ewes.

The frequency of abortions in Australian sheep has not been well studied, but it is widely accepted that up to 2% of ewes will abort between scanning and lambing in an otherwise healthy flock. In this study, mid-pregnancy abortion levels of greater than 2% were detected in 6/19 (32%) of the ewe lamb flocks. Importantly, only one of these flocks had obvious signs of abortion that would have been detected by the farmer with typical monitoring of the ewes.

There was no association between mid-pregnancy abortions and liveweight at joining, condition score at joining, liveweight change from joining to Scan 1 or litter size (singles or multiples).

Maiden Merino hoggets

On average, 29% of foetuses identified at Scan 1 failed to survive to lamb marking. Lamb mortality between birth and marking was the greatest contributor to foetal and lamb mortality for most flocks. As with ewe lambs, overall lamb mortality between scanning and marking was lower for lambs scanned as singles (30%) compared to lambs scanned as multiples (twins or triplets; 47%).

Mid-pregnancy abortions were less frequent in maiden hoggets than ewe lambs. Mid-pregnancy abortions were detected in 6/11 (54%) hogget flocks where 2 – 4% ewes were affected. The frequency of mid-pregnancy abortion was more than 2% of ewes for 2/11 (18%) flocks.

There was no association between mid-pregnancy abortion and liveweight at joining, condition score at joining or liveweight change from joining to Scan 1.

Discussion

Most lamb mortalities for maiden ewes occur during birth and the first few days of life, as is the case in mature ewes. However, abortions during mid-pregnancy were significant contributors to overall lamb mortality for some ewe lamb flocks in this study.

Mid-pregnancy abortions were greater than the widely accepted ‘normal’ level (2% ewes) for approximately one in three ewe lamb flocks. There was no evidence that either liveweight or condition score in early pregnancy explained mid-pregnancy abortion in these flocks.

Mid to late-pregnancy abortions were usually not readily noticeable with typical monitoring, even in the flocks where high frequency of mid-pregnancy abortion was detected using repeat scanning and confirmed with lambing records. Mid-pregnancy abortions are likely to go undetected in most flocks. In many cases, the first indication of a problem is discovered at lamb marking with disappointing marking rates and a high proportion of ewes dry based on inspection of the udder. Foetal/lamb losses from abortions are difficult to distinguish from losses that occur in the perinatal period without additional monitoring. Repeat scanning, lambing inspections and ewe udder assessment at marking can be used to identify flocks where abortions are contributing to poor reproductive performance.

Lamb survival was lower for multiple-born lambs compared to single-born lambs which is consistent with previous observations for predominantly mature ewe flocks.

Conclusion

Lamb mortality between scanning and lamb marking is highly variable for maiden ewe flocks. Perinatal lamb deaths occurring during or close to birth are the most important source of foetus/lamb loss between scanning and marking in most maiden ewe flocks, particularly for twin lambs. However, abortions are an important source of loss in some flocks, with mid-pregnancy abortions higher than expected for one in three ewe lamb flocks. Identifying flocks where abortions are causing losses should inform strategies to improve reproductive performance because strategies targeting perinatal survival are unlikely to address common diseases that cause abortions.

Key messages

- Abortions during mid-pregnancy were detected in 14/19 ewe lamb flocks and 6/11 maiden hogget flocks using repeated scans and lambing records

- 5.7% of ewe lambs and 0.9% of maiden hogget ewes aborted during mid-pregnancy. The frequency of mid-pregnancy abortion ranged from 0–50% for ewe lamb flocks and 0–4% for maiden hoggets

- Lamb mortality in the perinatal period (between birth and marking) was the greatest source of lamb mortality after pregnancy scanning in most flocks

- Abortions were an important contributor to overall lamb losses in some ewe lamb flocks

- Mid-pregnancy abortions are challenging to detect and likely underreported with normal sheep management and monitoring

Further information

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Meat & Livestock Australia. We thank the participating farmers who provided access to their animals and facilities and conducted lambing rounds. We thank Tom La and Nyree Philip (Murdoch University), Louis Lignereux and Rob Paterson (University of Adelaide), Andrew Whale, Mary McQuillan and Patrick Hannemann (Livestock Logic, Hamilton, Victoria), Sean McGrath (Millicent Veterinary Hospital), Simon Edwards and Michelle Smart (Willunga Veterinary Hospital), and Lauryn Stewart and Deb Lehmann (Kangaroo Island Veterinary Hospital) for assistance with sample collection.

Adapted for Ovine Observer with assistance of Sofia Testa (Murdoch University Bachelor of Agricultural Science student).

2021 and 2022 Southern WA sheep reproductive rates based on pregnancy scanning data

Katherine Davies DPIRD Northam, WA; Andrew van Burgel DPIRD Albany, WA

Author correspondence: katherine.davies@dpird.wa.gov.au

Introduction

Pregnancy scanning ewes for multiple foetuses has shown to be a valuable tool in sheep enterprises. In the October edition of the Ovine Observer, John Young reported that utilising pregnancy scanning information and adopting optimum management resulted in an average return on investment of 400% across all flocks and times of lambing.

Pregnancy scanning allows producers to implement tailored ewe management strategies based on the number of foetuses carried. Management strategies to optimise the reproductive and lifetime performance of the ewe and lamb can include differential supplementary feeding rates and paddock selection to ensure adequate nutrition, shelter and survival. The information can also be used to inform culling decisions, future genetic selection, determine the stage of the reproductive cycle where lamb mortality is occurring and early detection of reproductive failure (Young, 2022).

Pregnancy or Conception Rate (CR) is the number of ewes scanned pregnant per 100 ewes joined and can be calculated when doing wet/dry scanning. Scanning or Reproductive rate (RR) is the number of scanned foetuses per 100 ewes joined, therefore the number of lamb foetuses per ewe is counted. This can also be called scanning for multiples or litter size. RR is the potential lambing rate and adds valuable information to optimise management.

Pregnancy scanning data for Merino and meat breed ewes is collected on a yearly basis from scanning providers across southern Western Australia and excludes any artificially inseminated or ewe lamb matings. DPIRD has just over 2 million individual ewe scanning records from 2015 to the current season, with almost 1.3 million of those scanned for multiples.

The data is distributed across two zones: the cereal sheep zone (CSZ) and the medium rainfall zone (MRZ). The CSZ extends from the Geraldton area in the north west to the Esperance region in the south east and is known as the wheatbelt. The MRZ includes the whole south west, from the Perth area in the north, to Albany in the south and is known as the wool belt (Figure 1).

Pregnancy scanning data was collected for 2021 and 2022 across these two zones and stretches from Northampton in the north, through to Augusta-Margaret River, south to Albany and east to Jerramungup and Ravensthorpe. Larger collections of pregnancy scanning data came from the shires of Williams, Kojonup, Dandaragan, and Cranbrook (Figure 2).

Sheep pregnancy scanning benchmark tool

This online tool has been updated with the latest pregnancy scanning data for multiples from 2021 and 2022, and includes data back to 2016. Producers can benchmark their own flock’s reproductive performance against other Merino or meat breed flocks in the CSZ and MRZ with the same time of lambing.

This tool is available on the DPIRD website.

Conception and reproductive rates in 2021

Data was collected from a total of 555,000 ewes over 347 properties. The data consisted mostly of Merino ewes, but also included 55,000 non-Merino ewes across 44 properties. The non-Merino ewes had an average CR of 85% and an average RR of 133%. However, due to the small sample size, the non-Merino ewes were not included in further statistical analysis.

The average CR for the 500,000 Merino ewes across 303 properties was 90% (10% dries). The properties that scanned for multiples included 269,000 Merino ewes across 147 properties, and had an average RR of 127%, with most producers between 130-140% (Figure 3).

The reproductive rates for Merino ewes were not significantly different between the CSZ (129%) and MRZ (126%). The CSZ had significantly more twins (41% vs 35%) than the MRZ, which was offset by 3% more dries as summarised in Table 1.

| Zone | CR | Dry | Single | Twin | RR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSZ | 88% | 12% | 47% | 41% | 129% |

| MRZ | 91% | 9% | 56% | 35% | 126% |

CR was significantly higher for producers with larger flocks (>1000 ewes) at 90% compared to 86% for smaller flocks (<1000 ewes), however RR was the same (127%).

CR was not significantly different for producers that scanned for twins (90%) compared to producers that only scanned for pregnancy (89%).

Month of scanning in 2021

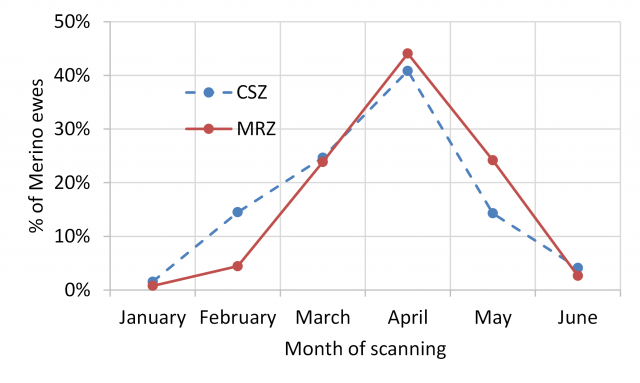

The time of scanning was earlier for the CSZ with 17% of Merino ewes scanned by the end of February, compared to just 4% in the MRZ at the same time (Figure 4).

The CR and RR increased as scanning month progressed. The CR for scanning in February (87%) was significantly lower than the CR for April (91%) (Figure 5). The RR was also significantly lower for scanning in February (111%) compared to April (131%).

Conception and reproductive rates in 2022

Data was collected from a total of 663,000 ewes over 386 properties. The data consisted mostly of Merino ewes, but also included 50,000 non-Merino ewes across 40 properties. The non-Merino ewes had an average CR of 85% and an average RR of 138%. However, like the 2021 data, the non-Merino ewes were not included in further statistical analysis due to the small sample size.

The average CR for the 612,000 Merino ewes across 346 properties was 89% (11% dries). The properties that scanned for multiples included 319,000 Merino ewes across 162 properties, and had an average RR of 133%, with most producers between 130-140% (Figure 6).

The reproductive rates were not significantly different between the CSZ (131%) and MRZ (134%). The CSZ had significantly more dries (14% vs 9%) than the MRZ, which was offset by 2% more twins as summarised in Table 2.

| Zone | CR | Dry | Single | Twin | RR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSZ | 86% | 14% | 42% | 45% | 131% |

| MRZ | 91% | 9% | 49% | 43% | 134% |

CR was significantly higher for producers with larger flocks (>1000 ewes) at 89% compared to 86% for smaller flocks (<1000 ewes). RR was also higher for larger flocks (133% vs 128%) however the difference was not statistically significant.

CR was significantly higher for producers that scanned for twins (90%) compared to producers that only scanned for pregnancy (88%).

Month of scanning in 2022

The time of scanning was earlier for the CSZ with 16% of Merino ewes scanned by the end of February, compared to just 5% in the MRZ at the same time (Figure 7).

The CR and RR increased as scanning month progressed. January and June were omitted due to little data for these months. The RR was significantly lower for scanning in February (124%) compared to May (136%), while the differences in CR were not significant (Figure 8).

Reproductive rate trends over time

Merino ewe RR has varied depending on the season, with the pattern in RR following the pattern in percentage of twins. There was a significant increase in RR from 2016 (123%) to 2017 (132%), followed by a significant decrease in 2018 (128%) which then remained similar for the following 3 years. The RR of 133% in 2022 was higher than any of the previous six years and was similar to the high RR of 132% in 2017.

For more information, please visit previous editions of the Ovine Observer, as well as the following DPIRD webpages:

- Sheep pregnancy scanning benchmarks tool

- Managing pregnancy in ewes

- Reproduction potential and marking rates of the WA sheep flock

Making the move to non-mulesed webinar: recording available online

Katherine Davies DPIRD Northam, WA

Author correspondence: katherine.davies@dpird.wa.gov.au

Recently DPIRD Livestock Development Officer, Katherine Davies hosted a webinar on making the move to non-mulesed sheep enterprise.

The webinar included former DPIRD researchers, Johan Greeff and John Karlsson discussing their research into the predisposing factor for flystrike as well as the indicator traits and Australian Sheep Breeding Values (ASBVs) that sheep producers can use to select to breed sheep more resistant to flystrike.

DPIRD Katanning Research Station Manager, Keren Muthsam, outlined the management of the non-mulesed flock at the station used for research or commercial purposes, and what had been learned in the journey since ceasing mulesing in 2008.

Sheep producers Thomas Pengilly and Emily Stretch shared their journeys in the shift to a non-mulesed enterprise. Key messages shared by both were the need to plan the transition, use breeding to increase resistance to flystrike, know when the high flystrike risk periods are and which are your most susceptible sheep. They also discussed the importance of having management practices and back up plans in place in case of a fly wave or delay in contractors.

AgPro Management’s Georgia Reid-Smith shared information about their MLA funded Producer Demonstration Site project; supported shift to non-mulesing systems in WA. This project is bringing together sheep producers in a group setting to share learnings and demonstrate best practice to increase producer’s confidence to make the shift.

Finally, Australian Wool Innovation’s Geoff Lindon went through the flystrike extension program which includes a suite of workshops for producers on flystrike management, chemical resistance, breeding and selection, and planning the move to a non-mulesed enterprise. Geoff also touched on AWI’s investment into flystrike research.

There was a wealth of knowledge and practical tips shared by all presenters with great questions from attendees on the considerations for the shift to a non-mulesed enterprise. The key learnings emphasised the need for:

- planning

- genetics and selection

- worm and dag management

- timing of shearing, crutching and chemicals

- know your enemy and use the tools available

- the webinar is available for viewing on DPIRD’s webpage Managing non-mulesed sheep.