The information in this page is only a guide – seek expert advice before planning, and use expert contractors for construction where necessary. Each landholder has a duty of care to make sure that flows from earthworks are not discharged indiscriminately on a neighbouring property and that stream flows are not significantly diminished or degraded.

See Conservation earthworks legal requirements of landholders for more information.

Important notice

Owners or occupiers of land must give at least 90 days notice to the Commissioner of Soil and Land Conservation of an intent to drain subsurface water to control salinity and discharging that water onto other land, into other water or into a watercourse. This includes discharging onto the same property. The notice must be in writing using the notice of intent to drain or pump (NOID) form.

Why use an evaporation basin?

- An evaporation basin allows direct control of discharge from drainage or pumping.

- On-farm evaporation basins avoid damage to neighbours and downstream environmental and infrastructure values.

- Small to large community-scale salt disposal basins can be used to impound saline water from community drainage and pumping systems.

- Salt can be harvested from the evaporation basin and sold or removed to a safe disposal area.

Basin design and leakage

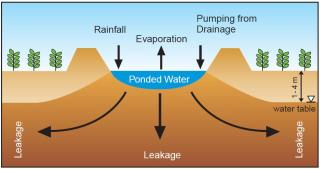

Build evaporation basins as part of an integrated farm or catchment water management plan. In Western Australia, many natural salt lakes act as evaporation basins for internally drained catchments. They form part of the ephemeral river systems that store water during low flows or small rainfall events. These natural salt lakes evaporate water and accumulate salts. Large run-off events periodically flush the lakes. Leakage to deeper aquifers below the lake systems removes some salt from the lake (Figure 1).

A constructed evaporation basin can consist of a single basin or a number of basins (Figure 1). Small to large community-scale salt disposal basins can be used to impound saline water from drainage and pumping systems installed to protect farmland.

Sealed basins

Sealed evaporation basins have an organic, clay or plastic liner installed to prevent saline water leaking from the basin.

Use sealed basins where:

- the risk of significant leakage is high

- the groundwater beneath the basin has the potential to become polluted from leakage

- there is a risk to downstream assets from leakage

- salt harvesting is proposed.

Installing a liner significantly increases the cost of construction, but also significantly reduces the risk of damage from salt leakage.

Leaky basins

Design and construct evaporation basins to minimise leakage of concentrated saline water.

- Basin leakage of about 0.5–1 mm a day is considered acceptable (On-farm and community scale salt disposal basins on the Riverine Plain, 2000)

- Leakage rates of greater than 3 mm a day reduce evaporation efficiency, and recovery of the leakage at these rates may become unmanageable.

- Design the basin with a leakage plan:

- forecast leakage based on site characteristics

- construct the basin to manage forecast leakage

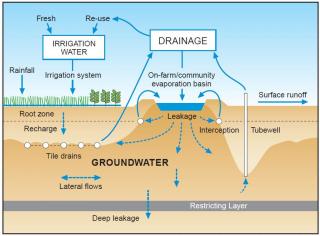

- have leakage recovery systems in place; use cutoff drains and pumps to capture most, if not all, of the basin leakage (Figure 2).

Natural salt lakes

Before using a natural salt lake as an evaporation basin:

- Assess environmental and nature conservation values and any restrictions. Natural lakes may provide habitat for threatened plants as well as having other important environmental values. Always contact relevant government agencies – including local government – as a first step in the planning process.

- Assess the lake's natural hydrology and leakage. Flood stripping (salt removed by large floods) can be used to dilute water salinity to safe levels before discharging.

Where to install an evaporation basin

For an evaporation basin to be effective and have minimum leakage, construct it:

- well away from neighbour boundaries

- in soils with low permeability

- in flat areas (with little watertable slope)

- in areas with shallow groundwater

- in soils that allow recovery of leakage

- away from the influence of flood events – unless designed to be stripped – and surface water run-off

- where there is high groundwater salinity, so basin leakage will have a limited effect on the groundwater quality

- away from built infrastructure, which may be at risk from leakage and to avoid problems associated with visual pollution and odours

- with adequate space for the structure to be expanded if designed inflows are exceeded.

Planning an evaporation basin

Design all evaporation basins to strict engineering and environmental standards. Comply with all legal and community approval requirements. The level of community consultation should reflect the scale and risk from each basin.

It is highly recommended that groups considering constructing an evaporation basin seek engineering design and related support from qualified contractors.

Evaporation basin guidelines for disposal of saline water (2004) provides guidelines for constructing and developing evaporation basins in WA. The primary steps in planning for an evaporation basin are:

- ensure that you have legal approval and have consulted the community

- determine the inflow from all sources (drain flow, run-off, and direct rainfall)

- determine the basin area

- determine the chemistry of run-off water, specifically pH and ion chemistry

- assess the physical and chemical conditions of the soil

- assess the environmental and social impact of the basin

- develop a ‘lifetime’ management plan for the basin.

Calculating inflow and basin area

Basin design, cost and operation depend on accurately estimating the daily inflow to the basin, and the relationship between the evaporative area, water salinity and depth.

Where large initial flows are expected after drain construction, stage drain construction over several years to optimise basin size and project costs.

Inflow calculations should include:

- estimates of average daily drain discharge (kilolitres per day), taking account of variations due to higher initial flows following drain construction

- storm flows (inflow of run-off) and direct precipitation (for example, using one in 10-year average recurrence intervals).

Use leveed drains to discharge into evaporation basins, to prevent surface water run-off reaching the basin. The basin must be contained by a continuous embankment (as a bunded ring or excavated basin), high enough to prevent overtopping.

Include known variations in inflow salt concentration in your calculations. The variation in salt concentration may affect long-term evaporation capacity and therefore size of the basin.

Evaporation rates are reduced when the salinity of water is increased: allow for 50–75% of reported pan evaporation rates in WA grainbelt evaporation basins.

Design basins to be of sufficient size to enable evaporation of annual inflow, but not allow the basin to dry out. Basin layout (multiple cells, several evaporators and crystalliser) and size will also depend on the basin water balance and salt-harvesting options. Several programs, such as BASINMAN, can help to estimate basin area.

Soil assessment

Test soil and water to discover the site variability: dig more deep soil pits in less-uniform areas.

Tests need to identify:

- the effect of wave action on the basin walls

- the effect of soil compaction by machinery and related monitoring infrastructure

- soil behaviour in the presence of high salt loads

- aquifer characteristics

- deep soil profile structure and texture

- variations in permeability, especially in the upper 5m

- watertable elevation and whether the groundwater level is stable or rising

- groundwater chemistry.

The major influence on leakage rate is usually the aquifer (deep soil) permeability, and the capacity of the aquifer to transmit water away from the basin. In WA, the effect of basin leakage is likely to occur close to the basin, because of low soil permeability and low hydraulic gradients that dominate grainbelt sites. This may limit the spread of leakage, but also makes capture of leakage difficult.

Environmental and social impact

Assess engineering-based risk on all potential sites. Increase the level of assessment as the potential risks to the environment and community increases. How would you manage the impact of basin failure?

Unsealed constructed basins

All unsealed evaporation basins tend to leak: design and monitor them to allow for groundwater recovery. Cutoff drains located around the perimeter of the basin, and tube wells downslope (Figure 2) can be used to intercept and monitor leakage before it has a major impact (note that using cutoff drains or tube wells will require notification to the Commissioner using a notice of intent to drain or pump water (NOID) form). Pump this water back into the basin.

Natural basins

For natural disposal basins (modified salt lakes), flood stripping (salt washed away by large floods) could provide a longer lifespan for basins. However, you will need to complete an environmental impact assessment before use. Base your design of such basins on detailed hydrology and downstream river hydrodynamics. In WA, assessment of hydrology and river hydrodynamics may depend on the seasonal variation of flow, given that a large proportion of creek and river systems are ephemeral.

Basin management plans

Basin design and management plans need to cover at least 50 years (JDA Consultant Hydrologists & Hauck 2004). This is especially critical where the system includes constructed basins, serviced by pumping from sumps. Include the ongoing high cost of pump maintenance and agreement on shared responsibility for cost and operation in the plans.

Factors to be included in the plan are:

- inflow (the amount of water, sediment, salt)

- salt movement within the basin

- harvesting and salt removal

- leakage

- bank stability

- basin failure

- other factors, such as odours, access, waterbird usage, monitoring and aesthetics.

Basin owners and managers are responsible for the consequences of their design, and require a notice of intent to drain or pump (NOID) to be submitted at least 90 days before discharge via drains or pumping can begin (see Legal and community approval below).

Basin owners, with support from local government and related regulatory bodies are required to:

- provide a plan

- gain necessary approvals

- monitor

- assess risks

- have contingency procedures

- plan and prepare for decommissioning

- produce a statement of accountability.

Legal and community approval

For catchment-based plans that include evaporation basins, relevant landholders and neighbours should be actively involved in the development and placement of the basin. The processes developed in the Beacon River Catchment – Salinity Management Project Feasibility Study are an example of the community consultation and risk assessment considered relevant when planning for the construction of a drainage and evaporation basin system.

There are legal controls on major earthworks associated with the construction of evaporation basins and the associated drains and pumping.

Have binding arrangements for funding ongoing operation and maintenance, and for continued access to drains on private land leading to the basin.

Notice of intent to drain or pump water

An owner or occupier of land must give the Commissioner of Soil and Land Conservation at least 90 days notice of an intent to drain or pump water where:

- the water to be drained or pumped is subsurface water

- the purpose of the proposal is to control salinity, and

- the water will discharge onto other land, into other water or into a watercourse.

The notice must be on a notice of intent to drain or pump water (NOID) form. For proposals to drain or pump surface or subsurface water within the Peel–Harvey Catchment, proponents must give at least 90 days written notice using the notice of intent to drain or pump water (NOID).

Proceeding with a drainage or pumping proposal without complying with the notice of intent provisions is an offence and can lead to prosecution. The maximum penalty is $2000 for an individual and $10 000 for a body corporate.

Environmental harm offences

A person failing to lodge an NOID when required to do so may face a charge of causing serious or material environmental harm under recent changes to the Environmental Protection Act 1986. Maximum fines for causing serious environmental harm are up to $500 000 for an individual and $1 million for a body corporate. Lodging an NOID with the Commissioner, and receiving no objection, is a defence where the construction and/or operation of such a drainage system causes material or significant environmental harm.

Other approvals

In addition to the above, approval may be required in the following cases:

- Some shire councils require development approval for certain types of earthworks, which may include evaporation basins. Check with your local shire to see if any approval is required before starting work.

- Where your evaporation basins may affect public land (such as a road reserve, rail reserve or conservation reserve), you must seek approval from the public authority responsible for that land, before starting work.

- If your evaporation basin requires the removal of native vegetation, or will lead to the destruction of native vegetation, contact the Department of Water and Environmental Regulation to enquire about permits.

- Watercourses in some parts of WA are subject to special controls, and may require the approval of the Department of Water and Environmental Regulation.

- Interference to the beds and banks of rivers and streams within a proclaimed catchment (Rights in Water and Irrigation Act 1914) is an offence, unless you have a permit from the Department of Water and Environmental Regulation.

- Wetlands (e.g. lakes and swamps) may be protected under state and national laws. Before constructing an evaporation basin that might interfere with a wetland, check with the state and national environment departments to see whether any approvals are required – in particular, the national Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 may apply.

- Always check that the excavation of an evaporation basin will not interfere with, or damage, telecommunication cables because repair costs can be significant.

Common law

You may also be liable under the common law for damage caused to a neighbour’s property by the construction or operation of a drain and evaporation basin. Diverting water from its natural flow channel may cause nuisance and trespass under common law. Seek written consent from any person who may be affected by the works, to minimise the risk of legal action for subsequent damages.

References

- JDA Consultant Hydrologists & Hauck, E 2004, Evaporation basin guidelines for disposal of saline water, Miscellaneous publication 3/2004, Department of Agriculture, Perth, accessed 15 March 2018.