Flystrike impacts the profitability of the enterprise, not only from loss of productivity from the individually struck animals, but also through the increased amount of time and cost of treating and preventing flystrike. Reducing the risk of flystrike has immense benefits to the health and wellbeing of sheep, the people who work with them and business/farm productivity.

There are five types of flystrike; both body and breech strike are seen as the most prevalent and important ahead of poll and pizzle strike. Risk of these types of flystrike will depend on environmental conditions as well as how susceptible sheep may be.

Predicting flystrike

Predicting your risk of flystrike will depend on environmental conditions as well as how susceptible your sheep are. Basic understanding of the Australian blowfly (Lucilia cuprina) and how blowfly larvae develop will also help in predicting flystrike.

Biology of the fly

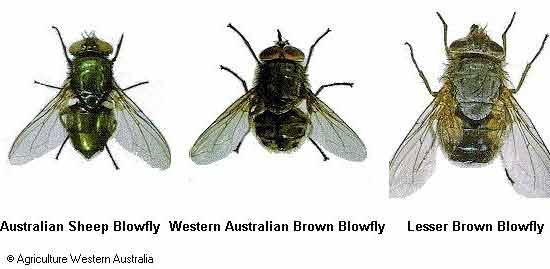

The main species of blowfly that initiates about 90% of all strikes is the Australian sheep blowfly. It is a copper green colour with reddish eyes. The adult fly is approximately 10 millimetres (mm) long and produces a smooth skinned white maggot. The damaged tissue and body fluid that oozes from the flystrike wound caused by L. cuprina attracts other species of flies. The hairy maggot fly, Chrysomya rufifacies is the most important secondary fly. It does not initiate flystrike, but readily invades flystrike wounds started by L. cuprina. It is blue green in colour, 10mm long and produces the characteristic hairy maggots.

Adult flies usually live for approximately two to three weeks. Eggs generally hatch into larvae in 12-24 hours and larvae grow from pin head size to 10-15mm in length within about three days. They then drop off the sheep — usually at night or in the early morning when ground temperatures are coolest — and burrow into the soil to commence pupation a day or two later. This means that a large proportion will subsequently emerge as blowflies from around sheep camps.

Adult flies will normally not travel more than three kilometres from where they hatch during their life span. After hatching, the female fly needs a feed of protein for her reproductive organs to mature. She needs a further feed of protein before egg laying. Common sources of protein are carcases, manure and existing strikes.

What are the perfect environmental conditions for flystrike?

- The presence of primary species (most commonly the Australian sheep blowfly).

- Temperatures must be right (between 15–38 degrees).

- Recent rain — enough to keep suitable sites on the sheep moist for about three days.

- There must be suitable sites (wrinkles, urine, faeces) on the sheep to attract flies and sustain larvae.

- Wind speeds below 9 kilometres per hour (km/h) as this gives flies the best opportunity to disperse.

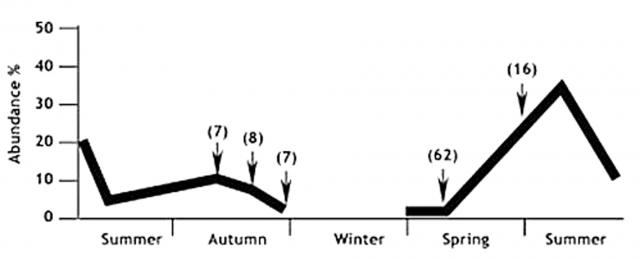

Figure 1 below shows the relationship between the abundance of L. cuprina and strikes, and shows that even low numbers can cause significant strikes. The strike incidence at Mount Barker Research Station in September 1978 was 62% of the total for the year — yet the number of L. cuprina was extremely low. Blowfly traps caught only one to two blowflies per trap in an eight hour trapping period. This indicates that the presence of any L. cuprina flies in traps is ample warning that there are enough flies to cause a serious strike problem if all other conditions for strike are ideal.

Studies have shown that L. cuprina are relatively inactive below 15°C and most active between 26°C and 38°C. The longer the temperature remains above 15°C the greater the chance of egg laying and dispersal. Wind speeds above 9km/h will reduce flight activity. They do not fly at all when the wind speed exceeds 30km/h.

How susceptible are your sheep?

Susceptibly depends on environmental conditions as well as sheep type and management strategies.

Best case scenario

- plain bodied sheep with low incidence of fleece rot and body strike

- hoggets have good worm control and rarely scour in spring

- lambs have low wrinkle level on their breech

- flocks have shorter (less than four months) wool during fly risk times in spring and autumn

- paddock monitoring undertaken every two days during times of high risk and effective flystrike treatment on-hand.

Worst case scenario

- highly wrinkled Merino sheep

- hoggets are daggy and with poor worm control

- flocks have long wool and are uncrutched/unshorn over high risk times

- sheep are rarely monitored and left to fend for themselves.

There are many options that will help you reduce your risk of flystrike. Genetic options are long term and permanent, making them a valuable tool in lowering your risk. In the short term, a range of husbandry options are also available.