Doug Smith and his wife Kerry are from Pingrup (250–275mm growing season rainfall). Doug crops 2500 hectares of wheat (50%), barley (20%) and canola, field peas and lupins (30%) and has had no sheep for the last 10 years. All his crops are sown no-till with one-pass knife points and press wheels.

Current attitudes to narrow windrow burning

Windrow burning first started in the northern section of the Western Australian wheatbelt around Geraldton. It was developed as a cheap and easy way to keep the lid on multiple resistant annual ryegrass and wild radish.

This area has a relatively short growing season and higher temperatures than more southern Australian cropping areas so windrow burning was a natural fit for this area. Cereal crop yields are generally less than 3t/ha and this has led to the idea that once crops are bigger than this, windrow burning isn’t possible.

The 2013–14 harvest has shown this is not true. Doug successfully burned windrows of crops over 5t/ha.

Doug windrows every year, even in paddocks with low weed numbers. He windrows all his crops, including pulses. Canola stubble is easy to burn and the fire stays in the windrows, generally burning hotter compared to other stubbles. Doug saves the canola stubble for burning in more difficult conditions as it is more predictable and always burns well.

Why windrow burn?

- to bring weed seed numbers down and keep them down

- chaff carts – burning in autumn is socially unacceptable (lot of fires escape 2-4 days after lighting) and Harrington Seed Destructors are very expensive (and new and a little untried)

- it is cheap to set up $300–$400 per harvester and can be done to any harvester

- it doesn’t slow down harvest

- paddocks are left with residue levels that stop wind erosion but do not cause trash flow problems at seeding

- reduced stubble levels are proven to reduce the risk of frost damage to flowering crops.

How to set up windrows

Size and type of windrows and over-threshing

- Aim to keep rows to about 500–600mm wide.

- Make sure chutes capture all chaff and weed seeds into windrow.

- Do not over thresh crops. This leads to rows with little or no airflow making rows smoulder rather than burn. Rows that smoulder do get hot enough to kill weed seeds.

- Make sure your chute does not restrict air flow from the cleaning fan of the harvester. Most chutes need to open back and front and closing the front leads to reduced harvest capacity in 4t/ha plus crops.

- Try not to run over rows with headers/chaser bins etcetera, as this crushes the rows giving the same result as over threshing

- Slow the harvester ground speed at the end of the runs so you empty the sieves at the same time as the rotors. This prevents tails of seeds with no straw mixed in to burn.

- The use of stubble mats to protect the front tyres of the harvester can help in forming a mini fire breaks along each side of the rows. The mats tend to lay down stubble at harvest when it is hot (generally it does not stand back up) so it is less prone to light up due to radiant heat coming from the rows when burning.

- Make sure the header knife is in good condition. This is very important if crops are lodged because blunt knifes tend to pull and lay ryegrass down in cool conditions rather than cut.

- Harvest the same direction the crop is sown. This is very important in heavy crops because the fire will carry down the individual rows that run away from the windrows.

- The exception to the above rule is if using old stubble rows to guide seeder bar steering (that is, when using I-TILL), you need to harvest at about 15 degrees to the way the crop was seeded. This is so you don’t end up with any rows left for the paddle to work with for a full run.

- Wider header fronts allow you to get better windrows in lighter crop years but can prove challenging when it comes to burning 5t/ha crop windrows. But the results are worth the effort.

Varieties and crop types

- Wheat varieties vary greatly in the type of residue that comes out of headers.

- Yitpi produces excellent rows with good retained straw size.

- Gladius produces finer residue that requires careful harvesting to achieve a reasonable burn.

- Wyalkatchem produces very poor windrows of almost powder like residue making it unsuitable for windrowing.

- Mace if treated right with the harvester will produce good rows, but is susceptible to over threshing in the heat of the day.

- Canola produces rows that will burn at the highest temperature for the longest period of time.

- Lupins also produces good row that will burn hot for the required length of time.

- Barley while some types produce good rows it can be tricky not to burn the whole paddock. The low fluffy flag can carry the fire between the rows.

- By changing from Gardiner to Hindmarsh, which produces a much better straw out of the back of the header, there are fewer problems with flat burning paddocks. This is because the rows are better suited to night time burning. The bigger windrows aren’t smashed allowing the straw to burn hot enough to kill seeds even when the Fire Danger Index (FDI) gets low so the fire won’t spread between rows.

- Doug has learned that even 4–5t/ha Scope and Buloke barley crops can be burnt very successfully, but you need to do everything right. With barley the conditions are the most important factor, with the humidity needed to be at 75%, the wind <12km/hr and temperature around 12°C. In our area these conditions generally occur between 9pm-3am. One 120ha paddock on Doug’s mate’s place this year took six hours to burn. There was a fair bit of stopping-starting waiting for the conditions to be right.

Burning and lighting

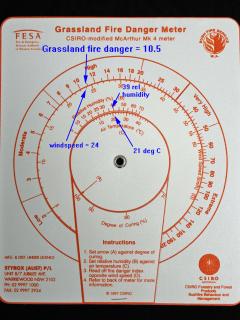

Doug uses the FESA McArthur Index (Figure 1), a scale used to calculate the fire danger in grassland using temperature, humidity and the wind speed to calculate an index. The scale gives a guide to the best windrow-burning conditions. As a rule of thumb, a Fire Weather Index of:

- less than 15 will give a reasonable burning result, but there is a risk of burning inter–row if windy.

- 8-10 is good and probably ideal.

- two and lower will not give a good result as it is too cold and humid. At this level the rows smoulder and will flare up when conditions warm up the following day burning the paddock bare.

- greater than 15 carries the risk of the fire getting out of control.

The online version is available at McArthur Grassland Fire Danger Meter Mk4. It should work on your smart phone/tablet, so you can use it in the paddock. Set 'Grass Curing' to 100% and then use your current weather conditions to estimate the grass fire index. Another useful resources is Fire Front Solutions' PocketFire app.

Useful pointers to remember

- There is no magic number, it changes every year depending on fuel load.

- If you don’t measure conditions and determine if you need a higher or lower fire danger index (FDI) you may be disappointed with the outcome (flat burnt paddocks, smouldering rows and still viable weed seeds).

- The FDI is a tool that Doug uses after he has determined what number he needs to aim for. (This year most of the burning took place between FDI of 2-8).

- Remember each of the three variables (wind, temperature and humidity) affect the FDI in different ways, some more than others.

- You can use meteogram weather forecasts for your area. Meteograms predict weather variables such as wind, temperature and humidity up to seven days ahead. There are a range of internet sites you can subscribe to. Doug has found the most accurate to be Willyweather and the Bureau of Meteorology MetEye - your eye on the environment. Both are free.

- Don’t guess the conditions, measure them and take a note of the result (every year is different so you may need to use a lower or higher fire index to get the right burn).

- There is a weather sweet spot for 2-3 hours each 24 hour period; you must be prepared to use this even if it is late at night.

- Doug has observed that shorter crops on lighter country often have lower, fluffy flag leaves which help the fire to spread outside the windrows.

- Always check burnt paddocks the next morning and put out anything left smouldering, this will reduce the chance of flare up when the day warms up.

- As a fire control officer, Doug has found that nearly all fires that require attendance are from rows left smouldering from the night before.

- Doug generally won’t burn when the forecast is for adverse conditions the next day (as it is his responsibility to issues burning permits he tends to cancel all burning permits when this is the case anyway).

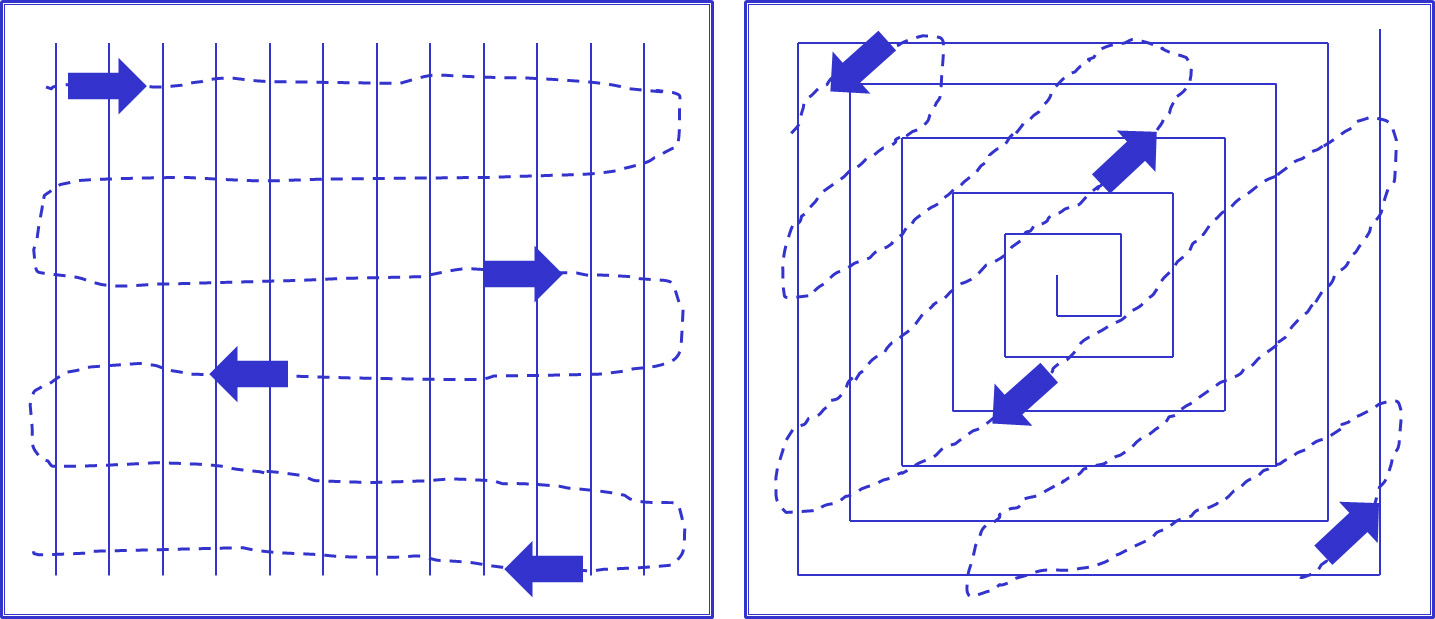

- Light windrows at 90 degrees across or diagonal to the windrow, rather than along the row as this prevents the fire developing a face which can carry between the rows (Figure 2). Ideally rows should burn to meet each other in 75m segments. In good conditions this only takes 25-30 minutes.

- Light up across the windrows every 75m in good conditions and plan to light much closer as conditions cool down. The fires will burn to meet each other.

- Best burning conditions are in the second half of March.

- Plan to commence burning just on dark when it is cooler but also plan to be finished burning when the dew falls (this limits stubble smouldering and subsequent flare-ups during the next day).

- This time constraint means that only 200-300ha (per team) can be burnt each night.

- Invest in a good fire lighters; Doug uses a gas/diesel powered unit mounted on a 650cc quad bike with a lighting speed of 30-40 kilometres per hour.

A final note: you cannot control all the weed seeds by windrow burning because you cannot get them all into the windrow. But done correctly you can keep weed numbers down even when things haven’t gone as well as you planned in crop.