The complex effects of fire

Fire, grazing and weather interact in complex ways to affect land condition and livestock production.

Recently burned pastures that are regenerating have relatively high productivity, diversity and palatability conditions that are important for many native flora and fauna species. Long-unburnt areas are important for providing breeding and shelter requirements of native fauna and for species with long life cycles, such as mature tree parasites, saprophytes and fungi.

We recommend monitoring rangeland condition, including response to fire, and adapting fire management to the needs of the pasture type, enterprise, management, safety and season. Fires affect land systems and pasture types in different ways and have cumulative effects over time.

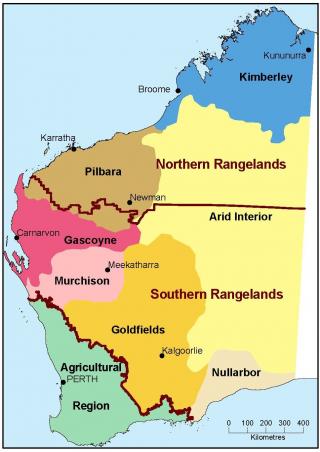

These guidelines for the Kimberley (Figure 1) are based on experience and available research findings, providing a starting point for fire management at the property scale.

The Kimberley is a highly fire-prone environment

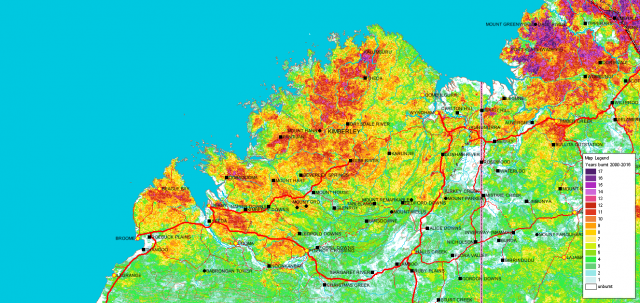

Kimberley rangeland managers operate in a highly fire-prone environment. A large proportion of the Kimberley region burnt frequently (7–12 times) in the years 2000 to 2016 (Figure 2).

Uncontrolled fires pose significant economic, safety and environmental risks to pastoral enterprises. In contrast, using controlled fire can benefit land management, livestock production and biodiversity conservation.

Reducing the risk of damage from fire

You can reduce the risk of damage from fire by following these steps:

- apply these general principles (linked below)

- use the visual fuel load guides available from the Department of Fire and Emergency Services (DFES)

- use the guidelines for managing pastures with fire in different types of country (linked below).

Research from the Kimberley and elsewhere shows that post-disturbance pasture recovery (including recovery from fire) is strongly correlated with favourable seasonal conditions and good total grazing pressure control.

General principles for managing fire

Uses and timing of planned fires

Most managers plan to burn early in the dry season (May to October) to reduce fuel loads and rejuvenate rank pastures; some use high-intensity fire to manage trees and shrubs.

- Low-intensity fires are used to remove unpalatable and low-digestibility mature grasses, allowing new growth.

- Moderate- to high-intensity fires are used to manage the balance between trees and shrubs versus grasses.

In general, early dry-season burns:

- are 'cooler' and less likely to kill trees and shrubs

- reduce overall pasture production in the year of the burn

- reduce production by perennials (especially if burned often and grazing resumes soon after fire)

- increase the proportion of production by annuals

- produce less greenhouse gas emissions than late dry-season burns

- reduce the risk of wildfires later in the season.

In general, late dry-season burns:

- are hotter and more likely to kill trees and shrubs

- have little effect on total annual yield

- may reduce the proportion of perennials, especially on red soils grazed soon after the burn

- have higher greenhouse gas emissions than early dry-season burns

- have an increased risk of damage from hot fires.

Maintaining the tree–grass balance

Burning can reduce tree and shrub density (woody thickening) in the productive grasslands of the tropical savannas. Tree and shrub density may increase to the point where grass production is reduced through competition for nutrients and water resources. Mustering is more difficult, and more expensive, where trees and shrubs have thickened up.

Deliberate use of moderate- to high-intensity fires to manage the balance between trees and shrubs versus grasses requires careful preparation and skilled management to prevent fires ‘getting away’. The taller the tree or shrub, the more intense the fire needs to be to kill these woody plants. For some trees, there is a critical height above which the population will be unaffected by fire intensity in the understorey of the natural vegetation.

DFES provides recommendations on conditions for producing fire intensities suitable for controlling a range of heights.

How flaming often?

This depends mostly on the pasture type, land system and climatic conditions preceding the burn. Details are given below for different rainfall zones.

Guidelines for managing pastures with fire in different rainfall zones

- High rainfall zone (above 700mm average annual rainfall)

- Intermediate rainfall zone (400–700mm average annual rainfall)

- Low rainfall zone (below 400mm average annual rainfall)

High rainfall zone (above 700mm average annual rainfall)

On more productive land (e.g. gently undulating red volcanic soils): fine-scale patch mosaic burning every 2–3 years early in the dry season is recommended, under the relatively low stocking rates that apply.

This fire regime can reduce the effects of selective patch grazing. Some burning after first storms can also be incorporated, provided that fires can be contained by low-fuel areas from earlier burning or other natural obstacles. A patchy mosaic of burnt and unburnt areas is desirable to provide cattle with access to mature bulk feed and more nutritious regrowth in adjacent areas.

On gravelly rises or rugged sandstone soils, and land where recovery after fire is slower: a lower frequency (every 3 or more years) is recommended. Plants in these areas are more dependent on regeneration from seed.

Areas around springs and rainforest patches require protection from fire wherever possible, particularly from hot fires (usually late dry season).

Avoid consecutive or annual burning

A regime of annual fires (particularly hot fires) is believed to favour annual native sorghum over the more desirable perennial grasses on light or sandy soils, and is likely to damage the ecosystem. Annual burning of the same area should be avoided.

Problems with wet-season burning

Problems with wet-season burning include:

- increased potential for soil erosion on slopes. Wet-season burning should not be undertaken on steep slopes. If wet-season burning on slopes is required, a patchy fire, ignited from a point rather than from a line-of-ignition is recommended

- increased risk of damage to geophytic species (that is, those species that regenerate from tubers, bulbs etc at the end of the dry season or start of the wet season). The evidence indicates there is likely to be limited damage to other species; in fact, many annuals and perennial herbaceous species will be favoured

- getting the timing right: if too early in the wet season – before about 100mm of rain has fallen – there may be ungerminated native sorghum seed left in the soil, and this will not be killed. If too late – after the monsoon has set in – the fire may not spread and the wet conditions limit access.

Benefits of wet-season burning

Annual sorghum can be eliminated where it is burnt after germination and before seedset because it does not have a persistent seedbank. This system can reduce fuel loads in sorghum-dominated pastures by 50%. However, the effectiveness of wet-season burning depends very much on timing.

Wet-season burning of annual sorghum results in:

- substantially reduced cover and density, but not necessarily the frequency of occurrence of annual sorghum

- substantially increased cover and frequency of the wiry perennial grass, Eriachne obtusa, and other perennial grasses generally

- an increase of herbaceous annual and perennial species, at least in the timeframe of 2 subsequent wet seasons

- a neutral to positive impact on the occurrence of individual herbaceous species; some species, especially sorghum, may decline.

Wet-season burning at the Bradshaw Field Training Area in the Northern Territory was highly effective at reducing fuel loads in pastures with an extensive cover of annual sorghum. These wet-season burns reduced fuel loads for at least 2 subsequent dry seasons and could reduce fuel loads for even longer. Wet-season burning can effectively reduce fuel at landscape and local scales.

Intermediate rainfall zone (400–700mm average annual rainfall)

Red soil pastures

Be cautious if burning pastures on red soil pasture types, especially if grazing animals cannot be excluded from the area after burning. Pastures on red soils tend to be less resilient to heavy grazing than those found on lighter or heavier soils, and red soils are often more prone to erosion.

Research from Kidman Springs in the Northern Territory showed that on red soil:

- 2-yearly fire suppressed perennial grass yield and promoted annuals and forbs

- 4-yearly late dry-season fire did not affect the total yield, although a higher proportion of annual to perennial grasses was observed

- 4-yearly early dry-season fire reduced the total and perennial grass yield and increased unpalatable forbs.

Burning small patches along tracks early in the dry season can lead to a concentration of grazing and subsequent loss of perennial grasses, especially if this practice is carried out year after year.

Monitor the density and height of shrubs. If shrub control is needed, consider spelling or reducing the stocking rate after the wet season to ensure an adequate fuel load remains for burning towards the end of the dry season (at least 2 tonnes per hectare). After burning a paddock it is preferable to defer grazing for at least several months after the rains begin, to ensure perennial grasses re-establish an adequate leaf area and rebuild root reserves.

Black soil pastures

Black soil pastures have relatively high carrying capacities and have traditionally been protected from fire.

Research from Kidman Springs in the Northern Territory showed that on black soil:

- 2-yearly or early dry-season fire reduced total yield by 15–20% and perennial grass yield by 25%, and increased annual grass yield

- 4-yearly late dry-season fire had little effect on yield or composition

- 4-yearly early dry-season fire reduced total yield slightly.

Burning can:

- encourage more-even grazing within large paddocks

- rejuvenate rank pasture

- allow a temporary increase in the legume and annual component of pasture, which may improve nutritional quality

- produce areas of lower fuel to break up large expanses of wildfire-risk pasture

- control woody shrubs.

Pasture production on black soils is more dependent on the amount and distribution of rainfall than on lighter soils.

How frequently and at what time of year should black soil pastures be burnt?

- We recommend a minimum of 4 years between fires.

- For pasture management, we recommend burning late in the season when the fire danger index has moderated; immediately after the first storms may be suitable.

Limestone grass pastures

Limestone grass pastures are dominated by the annual or short-lived perennial Enneapogon grasses. No obvious benefits from burning have been identified, and burning pasture in poor condition should certainly be avoided. Occasional burning could be used to control shrubs such as prickly mimosa (Acacia farnesiana), but the fuel load may not reach the required level to support the fire intensity required to kill the woody plants.

Pindan pastures

Pindan is the term used to describe the vegetation occurring over deep red and yellow sands in the West Kimberley. It is characterised by dense stands of wattle (Acacia spp.). The main pasture species are curly spinifex and ribbon grass. To keep the pasture palatable to livestock, we recommend burning late in the dry season, with at least 4 years between fires, with no grazing in the wet season following the burn.

Low rainfall zone (less than 400mm average annual rainfall)

In low-rainfall Mitchell grass pasture, Scanlan (1983) found that the basal area, total tiller number and dry matter production of Mitchell grasses were similar 2 years after fire, in burnt and unburnt areas.

The low rainfall zone is dominated by various forms of spinifex pasture. Post-fire regeneration is predictable in very general terms, with short-lived forbs and grasses forming an important component of the community for the first few years, before dominance gradually returns to spinifex. Growth periods are followed by intervals in which biomass changes little. The general advice given in the spinifex rangeland pastures and fire page also applies to the management of spinifex country in the low rainfall Kimberley zone.

References

Chilcott, CR, Jeffery, MR, Huey, AM, Fletcher, M & Whyatt, S 2009, Grazing land management – Kimberley version, workshop notes, EDGEnetwork Future Beef Program, Meat and Livestock Australia, Sydney.

Cowley, R, Pettit, C, Cowley, T, Pahl, L & Hearnden, M 2012, ‘Optimising fire management in grazed tropical savannas’, in Proceedings of the 17th Australian Rangeland Society Biennial Conference, Australian Rangeland Society, Australia.

Craig, AB & Hadden, DJ 2012, ‘The effects of fire on grazed Mitchell Grass pastures in the East Kimberley: a case study’, in Proceedings of the 17th Australian Rangeland Society Biennial Conference, Australian Rangeland Society, Australia.

Craig, A & Novelly, P (eds.) 2005, 'Fire management guidelines for Kimberley pastoral rangelands', Best management practice guidelines series, Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Perth, researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/lr_best/2/

Dyer, R, Jacklyn, P, Partridge, I, Russell-Smith, J & Williams, R (eds.) 2001, Savanna burning: understanding and using fire in northern Australia, Tropical Savannas Cooperative Research Centre, Darwin.

Florentine, SK 1999, Ecology of Eucalyptus victrix in grassland in the floodplain of the Fortescue River, doctoral thesis, Curtin University of Technology, Perth.

Scanlan, JC 1983, 'Changes in tiller and tussock characteristics of Astrebla lappacea (curly Mitchell grass) after burning', Australian Rangeland Journal, vol. 5, pp. 13–19.

Stretch, J 1996, ‘Fire management of spinifex pastures in the coastal and west Pilbara’, Miscellaneous publication 23/96, Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Perth.

Suijdendorp, H 1955, ‘Changes in pastoral revegetation can provide a guide to management’, Journal of Agriculture, Western Australia, 3rd series, vol. 4, pp. 683–687.

Walsh, D, Crowder, S, Saggers, B & Shearer, S 2012, ‘Early wet season burning and pasture spelling to improve land condition in the Victoria River District, NT’, in Proceedings of the 17th Australian Rangeland Society Biennial Conference, Australian Rangeland Society, Australia.