Snail damage

Snails cause damage in citrus orchards by feeding on ripe and ripening fruit, leaves of young trees and young tree bark. Fruit damage appears as circular chewed areas in the rind (Figure 1). The brown garden snail (Cornu aspersum) is the most common species of snail causing damage in citrus orchards in the south west of WA (Figure 2). Other snails that might cause problems for citrus include the White Italian snail (Theba pisana), Vineyard or common white snail (Cernuella virgata) and small conical snails (Prietocella barbara).

Damaged leaves have large chewed areas along the margins. Snails can cause severe problems in citrus orchards, where no-till weed control and sprinkler and low-volume irrigation create an ideal environment for snail development. They can also cause issues with irrigation management by clogging sprinkler heads and irrigation systems.

Reproduction and lifecycle

An understanding of the snail lifecycle is fundamental for the effective management of the pest. Snails are hermaphrodites which means they have both male and female reproductive organs. Even though they are able to self-fertilise, most snails will mate with another snail. The garden snail reaches sexual maturity between one to two years after hatching.

Aestivation

In summer, most snails will shelter in the canopy to escape from the heat. During this time they are largely inactive and enter aestivation (dormancy). Aestivation can last from a few days to months. Snails in this state can also be found sheltering on fence posts, at the base of weeds and grasses, in trees as well as under rocks or below the soil surface.

Compared to other snail species, the common garden snail may be more active during summer. Rainfall can trigger snail activity and they may move out of the canopy to feed temporarily. Movement will depend on the type of ground cover and availability of other foods in the orchard.

Egg laying

Autumn rains and changing environmental conditions will break aestivation and trigger movement. After aestivation is broken, snails will begin to feed, mate and lay eggs.

Snails can produce up to six batches of eggs in a single year. During the mating process each snail will lay around 80 eggs about 3-6 days after mating. Each snail digs a 2–4cm hole in the soil with its foot to lay the eggs which will hatch two weeks later (Figure 3).

Most egg laying occurs in winter but can continue if the soil remains moist. The common garden snail may hibernate during winter if temperatures are too cold by burying itself in the soil or at the base of plants.

Some egg laying can still occur in spring if soil is moist. As temperatures increase, snails will begin to find a safe place for summer aestivation. Snails will increase movement into trees at this time. Cultivation or other management practices which disturb snails on the orchard floor and remove their food source will cause increased movement into trees. Populations from surrounding areas can quickly migrate in to orchards to aestivate.

Monitoring

The key to effective snail control is regular monitoring. It is necessary to estimate how many snails are present before and after applying control measures. Early identification of population growth is essential for control.

Check in the early morning or in the evening when conditions are cooler and snails are more active. The density of snail populations can vary substantially across an orchard. If there are a wide range of snail sizes in the orchard this indicates that snails are breeding but if most snails are the same size they are likely migrating into the orchard from nearby infected areas. Migration can be minimised by focusing control efforts on the boundary and neighbouring areas.

Control methods

Snail management is a multi-step process that involves both cultural and chemical control including:

- monitoring snail numbers for assessing and targeting management

- baiting to reduce population

- pruning tree skirts to make it more difficult for snails to attack low-hanging fruit

- managing weeds and mowing inter-row to reduce shelter and food source for snails

- banding tree trunks with copper foil or a copper sulphate to prevent snails from climbing trees or spraying foliage with copper to deter snails.

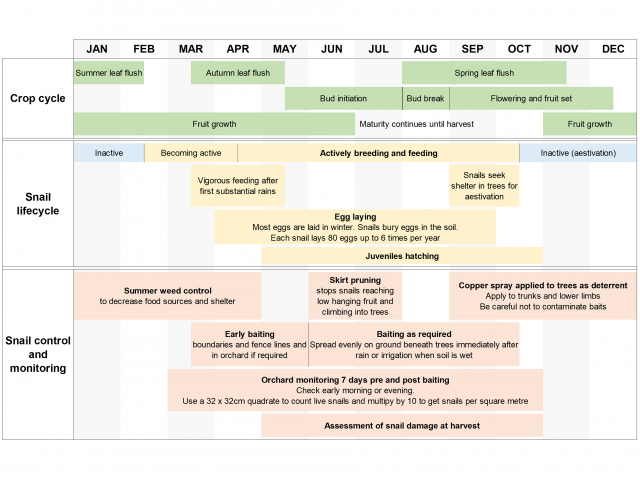

Figure 4 below shows an integrated approach to snail management over the year (click on the image to expand).

Cultural Control

Snails rely on humid sheltering refuges to breed and to protect themselves at certain times of the year (e.g. leaf litter, vegetation, rocks, fences and posts). Reducing their habitat by keeping weeds to a minimum and managing plant litter in the orchard will help reduce snail numbers.

It is important to keep the area under trees and the inter-row clean, tidy and free of weeds. Dense vegetation provides shelter for snails, and extra care should be taken for rows of trees near fence lines, where weed control may be difficult.

Skirt pruning helps to lift up lower branches so that snails cannot reach the fruit. Prune tree skirts 60 to 75 cm above the ground before the rainy season and apply a barrier trunk treatment. Barrier trunk treatments can be made with a band of copper foil or wire wrapped around the trunk but these need to be checked and renewed regularly.

Snails take refuge in tree guards. Guards should be removed as soon as is practicable. Snails don’t like crawling on rough or abrasive surfaces and, where guards are necessary, surrounding them with a layer of fine straw mulch may reduce the rate of infestation.

Chemical control

The current method for snail control in citrus orchards is the application of methiocarb, metaldehyde or Iron EDTA baits. Copper sprays have also shown some effect as a deterrent. Check labels or the APVMA website that the product is registered for and rates to use in the orchard. It is important to note that snail baits are poisonous if consumed by people or pets.

Baiting

Timing is essential for successful baiting of snails. Snails will only eat baits if they are active and looking for food. Baits are more effective if they are the only source of food, or when alternative food sources are less desirable.

Young snails (less than 7mm in diameter for round snails and 7mm in height for conical snails) are not likely to be controlled by baits.

Baiting should begin when snails begin to move and feed in early autumn and before they start laying eggs, usually after the first heavy rains of the season. This is also when snails are hungriest, after spending the summer months inactive and emerging when little alternative feed is available.

Follow-up baiting may be required as unhatched eggs could be present. Baiting in spring is not recommended for long term control. Snail populations are at their greatest at this time, and large numbers of snails are likely to survive a baiting program. There is also plenty of vegetation around so fewer snails are likely to take baits.

Bait immediately following an irrigation or rainy period when the soil is wet and snails are active. Bait must be on the ground before snail movement is triggered. Under sprinkler or low-volume irrigation, the baits will break down faster than in drier soil.

Application

When baiting, spread pellets evenly rather than in a concentrated heap or in a pile or narrow band. Bait can be applied with a fertiliser spreader or similar equipment that will evenly spread the pellets on the ground beneath trees. For existing populations within the orchard an even spread will give better control than a narrow band of baits placed directly under the trees.

Clear the ground surface before baiting by mowing or cultivating and spraying weeds. This will improve the performance of the baits. It is also a good idea to apply bait around the perimeter of the block in autumn or winter to help to control invading snails.

Effectiveness of different baits

The South Australian Research and Development Institute has conducted a comparison of the main snail baits used in Australia. See table 1 on the page New Insights Into Slug Control, which includes a cost comparison.

Recommendations on the effectiveness of baits:

- Baits often perform poorly and have to be re-applied due to field degradation and/or snail populations not actively feeding.

- Baiting with multiple applications rather than a single application of a high rate may be more effective.

- Rainfall erodes the physical integrity of bran-based baits and reduces effectiveness. This means snails are more likely to consume a sub-lethal dose.

- Temperature causes degradation of metaldehyde baits so when used over the summer they will not remain effective for more than two weeks.

- Commonly used bran-based baits need to be re-applied every two weeks; more expensive products will last three to four weeks.

- Iron-based baits should not be used when more than 10mm rain is expected.

- Small, even-sized baits are more effective.

Copper sprays

When snails are present in trees, copper foliar sprays may be necessary. Copper acts as a repellent to snails. Sprays as bands targeting trunks can act as a barrier. Spraying the whole tree can help move snails down to where the bait is at the base of the tree.

Do not mix copper products or other products with the baits to try to improve their performance as copper is highly repellent to snails and slugs and they will not eat a bait that has been contaminated with it.

If you are using sprays when you want to bait, apply the spray first, wait for it to dry, then apply the baits so they are not contaminated by the spray.

Barriers can be created around tree trunks to prevent snail movement onto trees. Products containing copper silicate are applied to the trunk and act as a repellent.

Biological control

Since all of our pest snails and slugs are introduced, there are limited agents that control them in Western Australia. Ducks, chickens or guinea fowl can provide effective, long-term control in orchards. Ducks, especially Khaki Campbell or Indian Runner varieties, are usually considered the best birds for snail control. Ducks need to be in a flock to operate efficiently. A flock of two dozen birds can control snails over an area as large as 20 hectares. For more information see Snail and slug control

Summary

- Snail control in citrus orchards requires an integrated approach including cultural and chemical management.

- Monitoring is essential for targeted baiting and control of snails before eggs are laid (autumn) and populations increase rapidly.

- Chemical baits are most effective when they are the only food source or where other food sources are not highly desirable.

References

AgNova Technologies Pty Ltd, ‘Snail Control in Vineyards’ http://cowag.com.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/173/2016/03/Metarex-vineyard-AgNote-1.pdf

Baker G. & Cunningham, N., 2016, ‘Small brown snail in citrus’, South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI), Available from: http://www.pir.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/285518/Small_Brown_Snail_in_Citrus_Fact_Sheet.pdf

Bound, S. 2004. ‘A preliminary model for slug control in vegetable crops’, Horticulture Australia Ltd, Available from: https://ausveg.com.au/app/data/technical-insights/docs/VG00030.pdf

Dekle, G.W. and Fasulo, T.R. 2003, ‘Brown garden snail’, University of Florida, Department of Entomology and Nematology, Available from:: http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/misc/gastro/brown_garden_snail.htm

Falivene, S. & Creek, A., 2017, ‘Citrus plant protection and management guide 2017’, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Available from: https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/agriculture/horticulture/citrus/content/manuals-guides/manuals-and-production-guides/citrus-plant-protection-and-management-guide-2017

Hetherington, S. et al. 2009 ‘Integrated pest management for Australian apples & pears’. NSW Department of Primary Industries, Available from: https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/321201/ipm-for-australian-apples-and-pears-complete.pdf

McDonald, K., Micic, S., Butler, A. 2018 ‘Snail Management Guide for WA Farmers’, Stirlings to Coast Farmers Inc. Available from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/559e60bbe4b01f3a7d5ca0bf/t/5b74e44db8a045d2f8b78097/1534387305313/SCF+Snail+Management+Guide+08+2018+web.pdf

Nash, M., DeGraaf, H., Baker, G. 2016, ‘Snail and slug baiting guidelines’, South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI), Available from: http://www.pir.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/286735/Snail_and_slug_baiting_guidelines.pdf

Nash, M. 2016. ‘New insights into slug control’, Grains Research & Development Corporation, Available from: https://grdc.com.au/resources-and-publications/grdc-update-papers/tab-content/grdc-update-papers/2016/07/new-insights-into-slug-control

Pietsch, A., Burne, P and Cotsaris, D., 2006. 'Snails in the Vineyard', CCW Co-operative Limited, Available from: http://www.ccwcoop.com.au/__files/f/4383/CCW%20FACT%20SHEET%205%20-%20Snails.pdf

University of California, 2017, ‘UC Pest Management Guidelines - Brown Garden Snail’, Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of California. Available from: http://ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/r107500111.html