Management factors affecting field establishment

Depth of sowing

Deeper seed placement delays emergence as it takes longer for the coleoptile (for cereals) or hypocotyl (for broadleaf crops) to reach the surface. Plant too deep and some may never reach the surface to become established as seedlings.

Definitions

- Hypocotyl is the stem of the germinating seedling that bears the seedling leaves (cotyledons) in flowering plants.

- Coleoptile is the protective sheath that encases the first leaf in monocotyledons such as grasses.

Deep sowing can also reduce plant vigour. This is because the seedling uses much of its stored energy for growing through the soil. The seedlings will be less vigorous upon reaching the surface.

As a rule of thumb, the seeding depth should be about five times the size of the seed.

The ideal sowing depth for wheat and barley are;

- Semi dwarf varieties: 20-35mm

- Down to 50mm for tall varieties with long coleoptiles. In some circumstances you can sow deeper to chase soil moisture but only those varieties with longer coleoptiles. Sowing at 80-100mm is reasonable when you are chasing moisture, but deeper than 100mm is not.

For canola, a sowing depth of between 12-25mm is ideal. Deeper-sown canola seeds grow longer hypocotyls which may result in shorter root systems and smaller leaf area. More information can be found at the Deep seeding in canola and Measuring sowing depth pages.

Cereal coleoptile length

Once the cereal seed has imbibed, the coleoptile can emerge. Once it emerges, it increases in length until it breaks through the soil surface. When the coleoptile senses light it stops growing and the first true leaf pushes through. If the seed is planted deeper than the coleoptile length, the shoot may emerge below ground and never reach the surface.

Varieties differ in their coleoptile lengths and those with shorter coleoptiles are less likely to emerge if sown too deeply.

Recent research however, has shown that larger seed has a much greater effect on crop establishment than variety when sown deep. Even within the same variety, large seeds have longer coleoptiles. Agriculture and Food research officer Bob French has found that seed size is particularly important for growers who choose to chase subsoil moisture. Results from Merredin and Buntine trials in 2014 showed that averaged over seven cultivars, large and small seed established the same number of plants when sown at 40mm deep in trials at Merredin and Buntine last year, but small seed established 28% fewer plants when sown 80mm deep.

For more information on coleoptile lengths listed for the different varieties refer to the 2019 Wheat variety sowing guide for Western Australia and the Barley variety sowing guide for Western Australia.

Note: Certain fungicides can reduce the length of the coleoptile and cause silly seedling syndrome. Coleoptile shortening can also occur with some herbicides such as trifluralin and pendimethalin.

Seed size

Seed size can play an important role in crop establishment. Larger seeds produce more vigorous seedlings and improved crop establishment.

It is recommended to grade out smaller seed to retain larger, high quality seed will improve crop establishment. Growers should use wheat seed that weighs at least 35 grams per thousand seeds, and preferably more than 38g per thousand seeds, especially if sowing at depth.

Average wheat seed weight under average conditions of common varieties are:

- Wyalkatchem: 37mg

- Mace: 35mg

- Yitpi: 33mg

- JusticaCL plus: 31mg

The size of a variety can vary a lot depending on conditions. Seed size was measured on 79 samples of Mace delivered to CBH in the Merredin zone in 2014 and seed size varied from 32.7-42.7mg with an average of 38.7mg.

Crop seed size is derived from a combination of genotype (variety or cultivar) and environmental factors during grain fill. Environmental factors may include;

- nutritional deficiencies such as molybdenum and potassium deficiency can reduce seed size and increase screenings

- low water or moisture stress at grain fill.

Row spacing

The most appropriate row spacing is a compromise between crop yield, ease of stubble handling, optimising travel speed, managing weed competition and soil throw and achieving effective use of pre-emergent herbicides.

As row spacing increases, there is a general trend towards poorer establishment due to competition for water or light from crowding of plants within the rows. The most efficient use of wheat seed is to sow it at narrow row spacing, giving each seed more room to germinate and emerge.

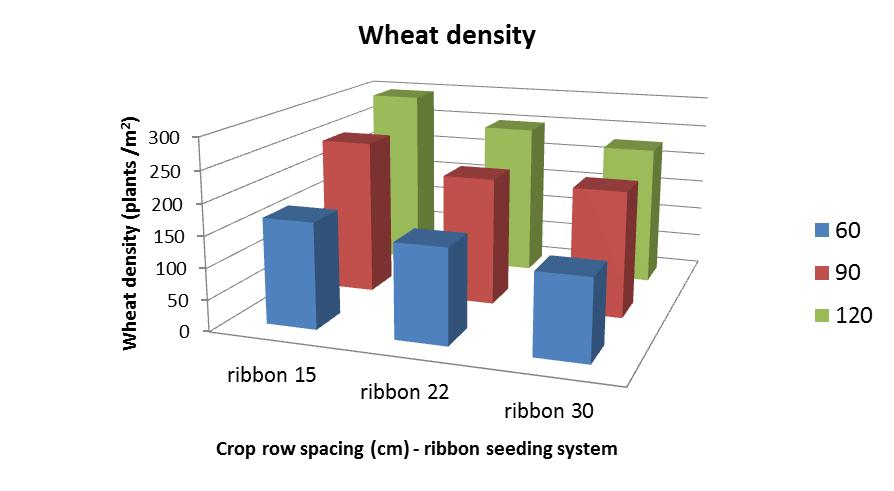

Work done by agriculture and food research officers Wal Anderson and Mohammed Amjad in 2005 found that increasing row spacing from 18cm, to 24cm and 36cm, established 9% and 21% less wheat plants, respectively. More recently in 2013, increasing the row spacing at Mingenew (while ribbon sowing, where a stiletto boot is modified to sow approximately a 50mm wide ribbon of seed), the percentage of wheat seed that emerged dropped from almost 100% at 15cm, to below 80% at 30cm. This percentage dropped further to 70% at a when the seeding rate was increased (Peter Newman from Australian Herbicide Resistance Initiative).

For more information on ribbon seeding and seed bed utilisation (SBU) refer to the GRDC factsheet, Fertiliser Toxicity - Care with fertiliser and seed placement.

Herbicides

Pre-emergent herbicides from Mode of Action Groups D (trifluralin; for example Treflan® and propyzamide; for example Kerb®), J (triallate; for example Avadex ®) and K (metolachlor; for example Boxer® Gold) can all affect seed emergence and establishment.

For more information refer to Diagnosing Groups D and J herbicide damage in cereals and Diagnosing Group K herbicide damage in cereals.

Good seedbed preparation

Preparation of a seedbed to ensure good seed soil contact is an important element in successful crop establishment. A cloddy seedbed may reduce emergence, as the clods allow light to penetrate below the soil surface. The coleoptile senses the light and stops growing while still below the surface.

High stubble loads at seeding time can impact on crop establishment and also reduce the efficacy of soil-activated preemergence herbicides. Disc machinery can handle heavier stubble loads than tyned implements but they can result in ‘hair pinning’ (stubble is bent rather than cut and pushed into the sowing groove with the seed), which reduces seed/soil contact. Equipment combinations including press wheels, coulter discs, trailing harrows can help manage stubble at sowing.