Life cycle

The worms are up to 2.5 centimetres (cm) long and occur in the abomasum or fourth stomach of sheep and goats. Female worms have a red and white striped appearance, hence the name ‘barber's pole’.

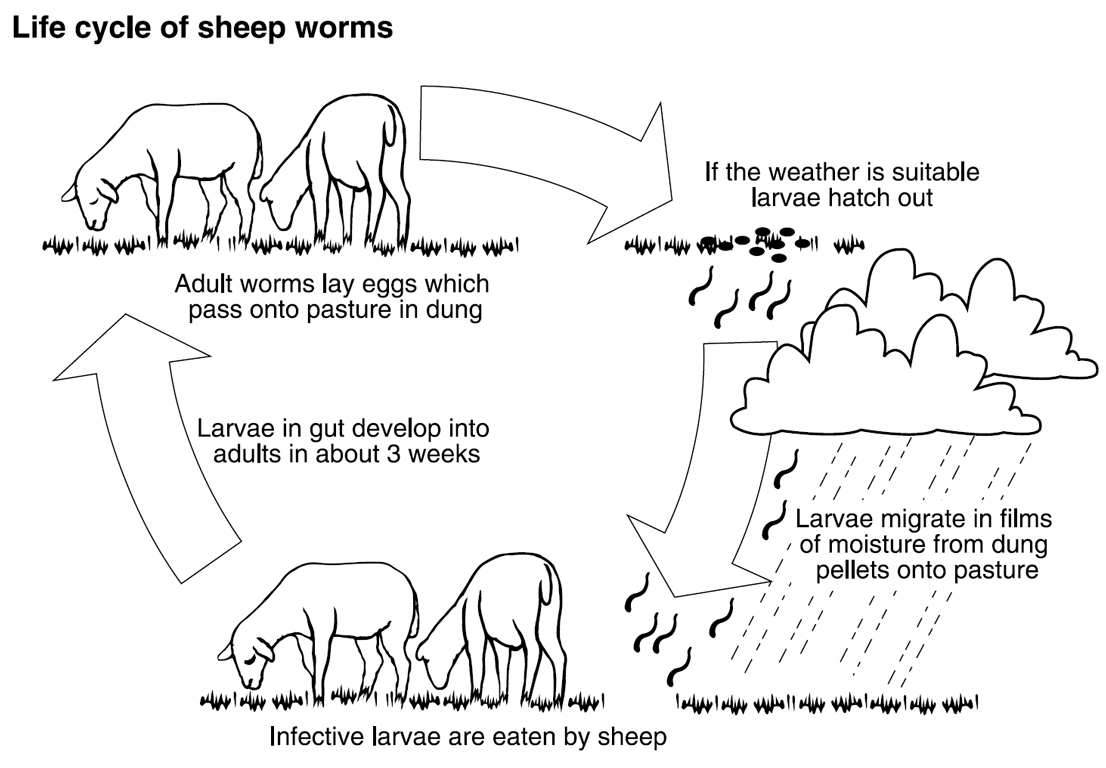

Their life cycle is typical of roundworms of sheep (Figure 1). Adult worms lay eggs which pass out in the faeces of the host. Barber's pole worms are the highest egg producers of all sheep worms. The eggs hatch within a few days and microscopic larvae emerge. They migrate on to the pasture, where they may be ingested with the herbage grazed by sheep. In the sheep’s gut, larvae develop into adult worms in about three weeks.

Distribution

Climatic conditions determine where barber's pole worms occur and when they are most prevalent during the year. The development of eggs and larvae is limited to areas and seasons where pastures are moist during the warm months of the year. However, the larvae can survive on pasture for some time, particularly during cool conditions and can can occasionally affect sheep at other times of the year.

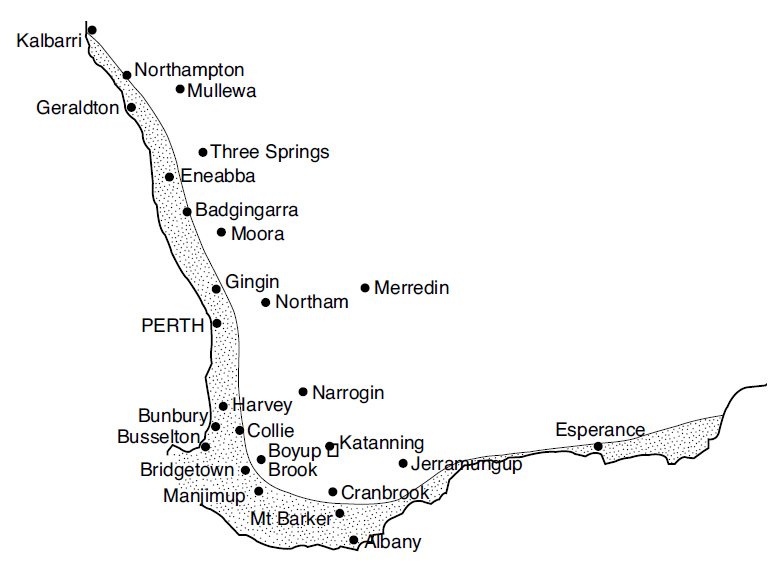

In WA, barber's pole worm is mainly a problem in the higher rainfall areas from late spring to early summer and from late autumn to winter. Where the annual rainfall decreases sharply as the distance from the coast increases, it is significant only in a narrow coastal strip. Elsewhere, such as on the south coast, it may occur more than 60 kilometres (km) inland (Figure 2).

The major areas are along the south coast from Walpole to Albany, where it may occur up to 60km inland, and further east in a narrower (20km) strip. On the west coast, problems are more sporadic and only occasionally occur more than 20km from the coast, but can occur from north of Geraldton and down to the Margaret River district.

In general, haemonchosis (the disease due to barber's pole worm) rarely affects sheep in areas where the rainfall is less than 600 millimetres (mm). However, outbreaks do occur in drier areas such as the central west coastal district if there is substantial rainfall during summer. There are occasionally outbreaks on northern pastoral properties, following successive wet years with prolonged heavy rainfall.

Sheep at risk

Sheep that have experienced a barber's pole infection develop an immunity that limits the size of subsequent burdens. This gives some protection against the severe effects of the worm but depends on the continued presence of some worms. If these worms are removed and no further contact occurs for some months, the immunity lapses and sheep may again suffer disease if they acquire large worm burdens.

Weaner sheep

Young sheep may experience massive infection before their immunity develops. Losses commonly occur in late spring and early summer and from the season’s break until early winter. Another danger period is after several days of heavy rainfall during midsummer. Generally haemonchosis does not become apparent until a month or more has elapsed after a period of infection.

Lambing ewes

Lactating ewes experience a temporary decline in their immunity to all worm species; this lasts for several weeks after they lamb. They can rapidly acquire a large burden of barber's pole worms during this time. With the added effect of poor feed quality and lactating demands, this can be fatal.

Sheep brought in from dry areas

Sheep from areas where barber's pole worm does not exist are highly susceptible to infection, even if they are mature. There can be losses even in adult wethers in good condition if they are grazed on a paddock heavily contaminated with larvae.

Signs of haemonchosis

Barber's pole worms suck the blood of their hosts and the signs of haemonchosis are related to the degree of blood loss.

In very acute cases, sheep may be found dead, with no prior signs of ill-health. Other sheep in the flock will be very weak and may collapse if driven. On examination, signs of anaemia are apparent: mucous membranes around the eyes and the gums will be white, rather than the normal pink. In these cases, sheep are often in good condition, although the effects are most severe in poorly nourished sheep. In less acute cases, the signs are similar but less dramatic. Some sheep may die but often the first sign is extreme weakness when sheep are driven for yarding. Affected sheep go down and show the typical signs of anaemia (pale gums and membranes).

A sign sometimes seen with barber's pole worm infection is the so-called ‘bottle-jaw’, a fluid swelling beneath the jaw. This is caused by a chronic shortage of protein in the animal’s bloodstream and is associated with a number of diseases, not only haemonchosis. Diarrhoea is not a feature of this disease. Mixed burdens of several worm species are common, and this is a major cause of ill-thrift, especially in younger sheep. The clinical signs in these cases often include weakness, poor performance and diarrhoea. A diagnosis is easily confirmed by finding a large burden of the worms at post-mortem.

Risk factors for haemonchosis

The likelihood of haemonchosis outbreaks is extremely difficult to predict, and varies from one year to the next.

Sheep losses due to barber's pole worm are relatively uncommon compared with the situation some years ago, possibly reflecting changes to farming routines and rainfall patterns. While this suggests that routine preventative treatment is often not necessary, it is important to be aware of weather conditions that favour barber's pole worm development and monitor worm burdens during likely risk periods.

History of occurrence

The best guide to the likelihood of an outbreak is the previous history of haemonchosis on the individual farm or in the district and how this varies with seasonal conditions.

Weather and season

Barber's pole worm larvae need warm conditions and moisture on the ground to develop. The risk of haemonchosis outbreaks is increased in years of late finishes to the season, early autumn breaks and when there is significant rainfall during summer.

Pastures

Barber's pole worm can survive where pasture remains green over summer. Typical situations include perennial pastures (especially kikuyu grass) and areas of moisture along creeks and around troughs and seepage points. Irrigated pastures pose an especially high risk.

Time of lambing

Ewes lambing from mid-May to early July are at the greatest risk, as the temporary loss of immunity to worms follows seasonal conditions favourable for barber's pole worm development (that is, due to larval pick-up in April to June).

Type of sheep

Sheep with a low or impaired immunity to worms have a greater risk of haemonchosis. This includes lambs and hoggets and ewes for two to three months after lambing. Wethers are at least risk, unless recently moved from a non-barber's pole worm area.

Controlling haemonchosis outbreaks

Burdens of barber's pole worm can increase rapidly, leading to large scale losses. Once an outbreak begins, the flock should be treated immediately. Even if outbreaks occur while ewes are lambing, it is best to yard and drench them despite the risk of mismothering lambs, as losses rarely cease without treatment. Ideally, the sheep should be moved onto a low worm risk pasture after they are drenched. If they must remain in the same paddock, they should be treated with a drench with persistent action (closantel or moxidectin), to prevent re-infection soon after treatment. Paddocks in which outbreaks of haemonchosis have occurred should be regarded as dangerous to sheep until a dry summer has passed.

Preventing haemonchosis

The long-term prevention of problems associated with barber's pole worm requires an effective worm control program and monitoring of worm egg counts. Whether specific pre-emptive action for barber's pole worm is needed depends on the risk level. The effectiveness of any preventative strategy is reduced where there is substantial summer green pasture or an early pasture germination.

A recently-developed vaccine (Barbervax) produced at the department's Albany laboratories provides protection from barber's pole worm infections when several vaccinations are given over the course of the main risk season. It will be especially useful where few treatment options remain due to severe drench resistance.

High risk situations

If haemonchosis has occurred on the farm during the year or it has been common in the district and seasonal conditions particularly favour barber's pole worm, weaners (lambs) should be protected by giving closantel with a summer drench (usually in December). Check worm egg counts 4-6 weeks after the season’s break or after prolonged summer rain to indicate whether additional preventative treatment is needed.

Ewes should be treated routinely with closantel 1-2 weeks prior to lambing, to protect them during the vulnerable period. Alternatively, worm egg counts can be taken two weeks before lambing is due to assess the risk. For wethers, the appropriate worm control program is usually adequate but monitoring worm egg counts 4-6 weeks after the season’s break is recommended to check numbers of all worm types.

Risk of haemonchosis may be increased where summer drenches are not given as part of programs aimed at reducing the development of drench resistance and additional monitoring of worm egg counts will be needed during risk periods.

Lower risk situations

When barber's pole worm is present in the area but haemonchosis is not common, using closantel is rarely justified if the worm control program is effective. Worm egg counts should still be taken at peak risk periods, as outbreaks can occur without warning. If conditions change to favour barber's pole worm development, for example, prolonged summer rainfall or a very early season’s break, specific preventative action may be warranted.

Safe pastures

The most efficient worm control strategies involve using safe pastures, that is, pastures with low levels of contamination with worm larvae. Sheep drenched on to a safe pasture in early summer should not need further drenches and there is no need to use closantel at this time. They should remain effectively worm-free for some time.

Brought in sheep

Sheep from areas where there are no barber's pole worms have no immunity to them. They should be carefully watched if introduced during the risk period of November to June.

Drenches

Most drenches available for control of roundworm in sheep are active against barber's pole worm. Resistance by barber's pole worm in WA has apparently developed only to the benzimidazole (white) drenches.

Broad spectrum drenches

Broad spectrum drenches remove all major types of sheep worms found in WA and include the benzimidazoles (white drenches), levamisole (clear drenches), the 'MLs’ (macrocyclic lactones: ivermectin, abamectin and moxidectin), and a new compound, monepantel. Products with various combinations of benzimidazoles, levamisole and MLs are also widely used.

Narrow spectrum drenches

Narrow spectrum drenches are effective only against barber's pole worm and include the active ingredient closantel (for example, Avomec Duel®, Genesis Xtra®, Closamax®, Closantel®, Closicare®, Seponver®, Sustain®) and the organo-phosphate naphthalophos (for example,Combat®, Polevault®, Rametin®). These drenches are preferred where only barber's pole worm is a problem. Combinations of organo-phosphates and other drenches also have a role against barbers pole worm (for example, Rametin Combo®, Combat Combo®, Colleague®, Napfix®).

Persistent action against larvae

Closantel and moxidectin have an important additional feature: they persist in the sheep for some weeks, killing barbers pole worm larvae as they are taken in during grazing. Closantel kills virtually all haemonchus larvae for at least four weeks after drenching and moxidectin (Cydectin®, Moximax®, Moxitak®, Sheepguard®, Topdec®) for at least two weeks. Moxidectin is also available in a long acting form that will give protection for 91 days (Cydectin LA ®, Mxaximus®).

Slow release capsules can provide persistent activity against all common worm larvae, including barber's pole worm, supplying drench over an extended period, usually 100 days. However, resistance is widespread to the active ingredients involved and complete effectiveness cannot be assumed. Also, there is a particular risk of drench resistance with long-acting formulations, as during the time of prolonged activity, only worm larvae of resistant worms can develop to become adult worms. For this reason, the use of long-acting products should be restricted to major risk situations.

Drench resistance

Resistance of barber's pole worm to drenches is not common in WA, although it is a major problem in parts of northern New South Wales and Queensland. A narrow spectrum drench (especially closantel) is the first choice where control of barber's pole worm is specifically required because using a broad spectrum type may promote resistance in other (non-target) worm species. However, other worm types are often present with barber's pole worm and a drench that controls all species may be needed.

Goats and barber's pole worms

Goats are considered more susceptible to roundworms (including barber's pole worm) than sheep. They should be treated according to the control programs recommended for sheep, using drenches available for use in goats. However, additional monitoring of worm egg counts is recommended.

Biosecurity

Livestock, machinery, fodder and people can introduce animal and plant diseases, weed seeds and pests. Develop a biosecurity plan for your farm to reduce the risk of these problems.

For sheep purchases, ask the vendor for an animal health statement which covers ovine Johne’s disease, footrot, lice, brucellosis, drenching and vaccination history.