Background

Twenty years ago, high levels of herbicide resistance in annual ryegrass were becoming a serious problem for many farmers in the area. Annual ryegrass has one of the highest levels of herbicide resistance worldwide, with tolerance to multiple herbicide groups, including glyphosate. As a result many farmers were struggling to control numbers, with one farmer claiming that when you picked up a handful of soil from the ground, “there were more seeds than soil.” This had detrimental effects on yield, due to light competition and weeds taking water and nitrogen from the soil.

As a way to combat this resistance, growers were experimenting with new and innovative ways to control numbers and creating a more comprehensive management approach than herbicides alone. This comprehensive management approach is known as integrated weed management (IWM), and has grown widely in popularity since then, due to its success at keeping weed numbers low and preventing further development of resistance.

Some examples of IWM strategies are the double knockdown, which involves applying two generalist herbicides (usually glyphosate and paraquat) in quick succession before sowing; the rotation of herbicide groups to slow down the build-up of herbicide resistance; and the mixing of herbicides in a single application to further prevent resistance. Other strategies include crop-topping, crop rotation, chemical fallows, grazing management, mouldboard ploughing, and crop competition. Harvest weed seed control (HWSC) is another tool in the IWM toolbox, which has been used with great success by a number of growers in the Geraldton region.

Former department officer, Peter Newman, was a vocal advocate for integrated weed management and took particular interest in the benefits of HWSC. As its name describes, harvest weed seed control takes place at harvest, and may involve one of a range of interventions designed to prevent weed seeds which are captured by the header from returning to the soil. Commonly adopted techniques include the use of chaff carts, narrow windrow burning, chaff lining, and chaff dumps. More recently, seed mills such as the Harrington Seed Destructor have also gained in popularity.

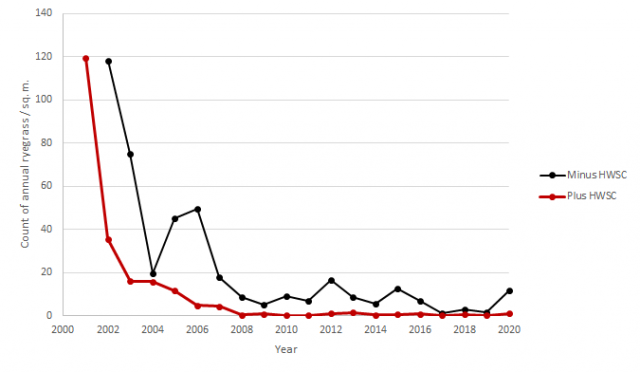

To gauge the effectiveness of these methods on-farm, Peter collaborated with farmers to monitor about 30 “problem paddocks” with known herbicide resistance. The average number of annual ryegrass per square metre were counted annually beginning in 2001, along with the herbicides used and any HWSC applied that year. He continued this monitoring for 16 years before exiting the department, and the project has since been continued by DPIRD. This is the twentieth year of the survey and has yielded some interesting results in that time.

Results and discussion

In Figure 1, “Plus HWSC” is defined as paddocks where HWSC was used in at least four years over the study period. In their first year, HWSC paddocks all averaged over 100 plants/m2 and non-HWSC paddocks over 300, but in only a handful of years all were reduced to single digits. In the first few years, strategies used by the farmers to bring the weeds under control were numerous and diverse. Livestock were more common at the time and many adopted the use of spray topping of pastures in the paddock. Lupins were crop-topped, some farmers burnt their stubble after harvest, and some even made the tough decision to sacrifice their crop and spray it out when ryegrass numbers became too out of control. Crops were rotated which allowed a more diversified herbicide regime, and double knockdowns were used when possible.

The HWSC methods commonly used were windrow burning, chaff carts, and chaff lining. Windrow burning involves placing all of the stubble into windrows at harvest and burning it. Having concentrated lines increases the temperature at which it burns, thus killing a higher percentage of seeds. Chaff carts are towed behind the header and collect the chaff directly from the header, which is dumped later to be burnt or fed to livestock. Chaff lining simply involves dumping the chaff onto the wheel tracks behind the header, which is a low-cost but still a relatively effective method.

Nowadays, pastures are much less common, and as an alternative some growers make use of a chemical fallow the weed numbers have risen too high. Mixing of herbicides in application has become more common, and in the last five years seed mills such as the Integrated Harrington seed destructor have also become popular. These take the residue directly from the header and physically grind it, destroying over 95% of seeds, before spreading the residue back over the paddock. Roundup ready® canola has also provided another avenue for chemical control.

Interestingly, once the weed numbers were under control, paddocks where HWSC was adopted were on average much more successful at keeping near-zero levels of weeds. This makes sense when you consider that 60-70% of weeds can be captured at harvest, and over 95% of weed seeds captured are physically destroyed by these methods. Some farmers are even at the stage where they have run the seed bank down low enough that they feel confident in reducing chemical usage. In fact, wild radish is generally considered to be more of a concern these days, but luckily many of the same strategies are just as effective on this weed as they are for annual ryegrass.

In this current year (2020), weed numbers in non-HWSC paddocks have increased to an average of 11.6 / m2, while in the HWSC group numbers are just below 1 / m2. This sudden increase may be attributable to the exceptionally strong wind event which occurred in late May.

Conclusion

Most farmers now feel that they have a good control over their ryegrass numbers, and comment that either brome grass or wild radish are their biggest concern. Luckily the strategies used to control ryegrass are transferrable to these weeds also, as their heads are relatively upright and can be captured by the header at harvest.

This survey has allowed growers to see the level of control which can be gained by incorporating HWSC into their practice, and how a wide variety of weed management strategies combined can give growers the confidence that they can continue to successfully control weed numbers and to continue their cropping rotation long into the future.

References

- Focus Paddocks: Case studies of Integrated Weed Management. Peter Newman & Glenn Adam

- Focus Paddocks: Case studies of Integrated Weed Management 2nd Edition 2009. Peter Newman

- Focus Paddocks: Case studies of Integrated Weed Management 3rd Edition 2013. Peter Newman

Acknowledgments

The department thanks all of the growers involved in the focus paddocks study who were willing to have their paddocks continually monitored, although the initial project finished in 2012.

Thank you to Peter Newman for his assistance in providing detailed insight into the study and IWM.

Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC) for their support of this work being continued within the Regional Research Agronomy project (DAW00256).

GRDC project number: DAW00256 (Building crop protection and crop production agronomy research and development capacity in regional Western Australia).